Big Trees, Early Years

by Frances E. Bishop and Judith Cunningham (Marvin), 1988

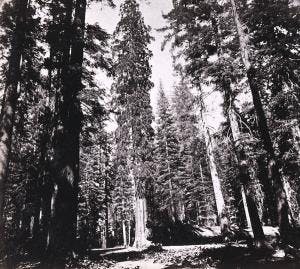

Certainly the groves now known as the Calaveras Big Trees were known to prehistoric populations. Among the earliest Americans to claim discovery were John Bidwell, who asserted that he traveled through the grove in 1841 on his way over the Sierra Nevada. Several emigrants, including the William B. Prince party, the Flanders party, and a Missouri doctor, recorded their impressions of the North Grove as they traveled westward in 1849 (Bishop, personal papers). As several emigrant diarists recorded their travels throughout the grove prior to 1852, the early Emigrant Road must have run through, or near, the present Park. Credit for the effective discovery, however, was given to Augustus T. Dowd, an employee of the Union Water Company of Murphys, who came upon the grove while on a hunting expedition in 1852.

This discovery created tremendous excitement throughout California and many rushed to the area to view these mighty giants for themselves. It wasn’t long before ways were found to make money from the public desire to experience these formidable wonders. In the spring of 1853, Captain William H. Hanford, president of the Union Water Company, viewed the Big Tree and envisioned a way to make a fortune by stripping the bark and sending it on tour to New York and Europe. The bark was exhibited first in San Francisco and then New York, where it was consumed in a fire. After stripping the bark, the tree was felled by using pump augers and chisels, as no saw was large enough for the project. The task took three weeks and an account in the San Joaquin Republican remarked that it fell on June 27, 1853. The Big Tree stump then became the focal point of the grove, roofed with a canopy of canvas and cedar boughs. A nearby well furnished ice cold water. The floor of the stump was planed smooth and dancing became a popular activity on the Big Stump, as did attending concerts, lectures, weddings and other functions.

The first mention of a structure in the grove is recorded in an account by Eliza Palache who was told by Helen Mary Whitney (a visitor to the area in 1852 with James Sperry and A.T. Dowd) that ” …a rough log cabin was built and a clearing made” (Palache n.d.). No record of the builder of that cabin has been discovered but, shortly thereafter, on July 19, 1853, William W. and Joseph M. Lapham filed land claims to two 160-acre parcels in the North Grove. This first cabin was replaced with the “Mammoth Tree Hotel” (Big Tree Cottage) constructed by William Lapham and Samuel Smith (who had invested $1200 in the enterprise). Although no record has as yet been found establishing the date the Cottage was actually built, it was probably shortly after the land claim was filed. A newspaper account of a trip to the Big Tree mentioned that Lapham was clearing the land in the summer of 1853 and that people were traveling to the grove on the Sperry and Strange Road (Sonora Herald, June 1 and June 11, 1853). In October 1853, William purchased Joseph’s interest for $800.

Lapham must have deeded a portion of the property to G.S. and Mary Smith, as they sold a one-third interest to John M. Brays on February 25, 1854. There is no further information on the Smiths, but possibly they loaned money to Lapham so that he could maintain control of the property. Brays was only briefly involved in the enterprise, selling his interest to Lapham on September 6, 1854.

The 1853 hotel was a two-story gable-fronted structure built within twenty feet of the Big Stump (Anable 1854). Also constructed at this time (with the financial assistance of the new partner, Samuel Brays) was a barn and a connected bar room and ten-pin bowling alley, the latter located on top of the fallen Big Tree and covered with shakes probably made from a section of that same tree. Lapham evidently ran into financial difficulties with this enterprise, as his carpenter, William M. Graves, filed a lien against the property for $185.00 for construction of a “dwelling house, bowling alley and barn.” According to a lumber lien filed in July 1854, by Richard E. Schonyo & Co., the lumber for the Cottage and Ten Pin Alley cost $334 for 6,680 board feet and was delivered in May and June of 1854 (Book A of Mechanics Liens, pp. 45-47).

These liens were satisfied September 9, 1854 by paying off Sylvester W. and James G. King. Although the identity of the Kings is unknown, Dr. A. Smith Haynes evidently provided the money and obtained first a one-third and later a one-half interest in the property from Lapham. Business must have improved with this partnership, as a two-story addition to the original hotel was constructed in 1854. This addition was attached to the original structure in an L shape. It had a gable roof and a veranda on the west side.

Nancy Jane Lapham, wife of William Lapham, was mentioned as being the hostess at the “Washington Mammoth Tree Grove” in the summer of 1854. Unfortunately Nancy Jane was already seriously ill with tuberculosis. On July 1, 1856, the Lapharns sold their interest in the Big Trees to Simon Schaeffle and moved to Murphys.

In May 1857, A. Smith Haynes held a Grand Ball at the resort. An "…excellent spring floor was laid between the hotel and the Big Stump and both the floor and stump covered by an arbor of cedar boughs beautifully arranged with many candles among branches…. The scene was romantic and beautiful beyond description" (San Andreas Independent; May 1857).

Local newspaper accounts mention that the Fourth of July was the most popular holiday at the Mammoth Tree Grove. Dances were held on the Big Stump, followed by a midnight supper. Ladies complained, however, “that there was no ‘spring’ to that floor!” (Hutchings 1886:222).

Haynes became the sole owner of what he now called “The Mammoth Tree Grove Hotel” on July 14, 1857, when he purchased the Schaeffle interest. He made extensive improvements to the grounds and buildings with a $3,000 loan from James L. Sperry and John Perry (proprietors of the well known Sperry and Perry Hotel in Murphys) in August of that year. By May 1858, the improvements had been completed. One of these was the Haynes’ Addition: a one-story, gable-fronted dormitory with Gothic Revival trim and an imposing front portico supported by four columns. This building appears in several photographs and stereopticon views taken during the mid 1860s and early 1870s, directly behind the "Chip of the Old Block." The Big Tree Bulletin and Murphys Advertiser, published on the Big Stump in 1858, also mentioned that the “Big Tree Stump is enclosed by an arbor extended to the hotel to make a spacious dining room (Big Tree Bulletin and Murphys Advertiser, May 21, 1858).

An article in another local newspaper of that same year stated that:

"Mr. A.S. Haynes, proprietor of the Big Tree Grove, has re-fitted and re-furnished his Hotel for the accommodation of customers in a neat and comfortable style. As a fashionable resort, the Hotel is equal to any in the State, and parties visiting the Grove, can go, assured that everything necessary for health or recreation is provided in a liberal manner. One of the peculiar features of the place is that the best of care and attention is bestowed upon all—adding a homelike charm to the many advantages of the place" (San Andreas Independent, May 22, 1858).

Haynes evidently envisioned a long-term occupation of the property as he cultivated 30 acres of land and raised 25 tons of oat and barley to feed the teams bringing visitors to the Grove, emigrants from the east, and freighters hauling loads to the Carson Valley. He also planted 75 tons of Lady Finger potatoes and a large quantity of garden vegetables. He planned to establish a botanical area to preserve and cultivate numerous native flowers and plants (San Andreas Independent, May 28, 1858).

The state of the economy, along with possible poor business management, was to kill Haynes’ grandiose plans. Events leading to the financial panic of 1858, the loss of many miners to the Fraser River gold strike, and the general depression following the California Gold Rush, sounded the death knell. The Mammoth Grove property was sold at a Sheriff’s sale December 26, 1857, to George Fisher for $137.07 in unpaid taxes for the years 1856 and 1857. Fisher was granted a deed on July 28, 1858 which he sold October 6, 1858 to Smith Mitchell, James L. Sperry and John Perry for $550.

These owners again changed the name at this time to the “Mammoth Grove Hotel.” They were absentee owners and hired Messrs. Danforth and Hooper as the legal hosts (as required by the sale). A. Smith Haynes, however, continued to operate the summer hotel on the property with his bride Julia Bishop as the contest for ownership continued.

Bayard Taylor visited the Mammoth Grove in the summer of 1859, and published his reminiscences in an article in the New York Mercury. He arrived as the sun was setting and described his trip thusly:

"Beneath the Sentinels ran the road. In front, a hundred yards further, stood the present white hotel, besides something dark, of nearly the same size. This something is only a piece of the trunk of another tree, which has been felled, leaving its stump as the floor of a circular ballroom, 27 feet in diameter… Seating ourselves on the veranda, therefore, we proceeded to study the Sentinels… Our quarters were all that could be desired, venison, delicious bread and butter and clean beds all made us regret that our stay was so limited" (Knight n.do:85,86).

In 1860, Sperry and Perry became the sole owners of the property, purchasing Mitchell’s share and paying Haynes (who had moved to Tuolumne County) $1,000 for his interest. In the summer of 1861, they constructed the new Mammoth Grove Hotel which could accommodate 60 lodgers. This was located up the slope, some six hundred yards northwest of the Big Stump and Big Tree Cottage. It is presumed that the old, original hotel was removed as this time as it does not appear in Vischer’s 1861 drawing. According to Edward Vischer:

"A spacious structure has replaced the original Big Tree Cottage: the foreground of the hotel was to have been laid out as a park, the ornamental shrubbery of which would have formed a striking contrast to the giant proportions beyond" (Vischer 1862).

Hutchings noted that “many hundreds of trees had to be down ‘to let in a little sunlight’ to the hotel site” (Hutchings 1886~219).

An emigrant family traveling through the grove in the summer of 1862 mentioned that the Bar Room and Ten Pin Alley were still standing. They were not to survive long however, for they were crushed by snow the following winter of 1862-1863, the wreckage remaining on ground for many years (Houseworth n.d.; Palmquist 1982). Also in 1861, the cedar bough and canvas pavilion over the Big Stump were replaced with a wooden structure by Sperry and Perry as a protection against the elements. This pavilion survived until 1934 when crushed by snow.

According to informants Ken and Doris Castro of Murphys, who uncovered a reference in a Stockton newspaper, the Big Tree Cottage burned in a fire in August, 1864. This information presents something of a mystery, for the Big Tree Cottage constructed by the Laphams appears to have been gone by 1861 (Vischer 1862). One theory is that the Cottage, or part of the Cottage, had been moved in 1861 to another location where it later burned. The fate of Haynes’ Addition is unknown: it was still in evidence in a photograph of the Big Stump taken ca. 1880-1885, and does not appear on the 1898 Big Trees U.S.G.S. Quadrangle map.

The other structures within the original Big Tree Cottage complex were the Barn and the Bath House. A large gable-roofed barn with flat-roofed extension on the east side appeared about 50 feet north of the Cottage in Ayres’ 1855 lithograph. A flat-roofed structure in this altitude of heavy winter snows does not appear practical; but perhaps the artist took his proverbial license (as he did with the orientation of the Bar Room in this same drawing). An 1871 account of a visit to the Grove mentioned a Bath House located over the creek. The exact location of this structure has not been ascertained, however Frances Bishop located several 12 by 12-inch posts, forming a 10-foot square, north of the Haynes' Addition and near the creek (Bishop 1977).

References

Anable, Henry Sheldon

1854 Diary of 1854. Sheboygan City Times, Sheboygan, Wisconsin. Copy in possession of Francis Bishop.

Big Tree Bulletin and Murphys Advertiser.

1858 Big Trees. J. Heckendorn, editor.

Bishop, Frances E.

1974-1988 Personal Papers, Arnold, California

Calaveras County Museum and Archives, San Andreas

1854-1865 Lien Books.

Houseworth, Thomas & Co., San Francisco.

n.d. Stereoptican views. On file at Calaveras Big Trees State Park.

Hutchings, J.M.

1886 Yosemite Valley and Big Tree Groves, A Guide to California’s Natural Attractions. Pacific Press Publishing Company, Oakland, California.

Knight, William H.

n.d. Scrapbook, Vol. 1-2. Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

Palache, Eliza

n.d. Annals of a California Family. Unpublished manuscript on file Calaveras County Museum and Archives, San Andreas, California

Palmquist, Peter E.

1982 “Don Rafael’s Tree.” In History of Photography, 6(1), January.

San Andreas Independent

1858 San Andreas, California

Sonora Herald

1853 Sonora, California

Vischer, Edward.

1862 The Mammoth Tree Grove and Its Avenues. Original lithographs at Calaveras County Museum and Archives, San Andreas, California.