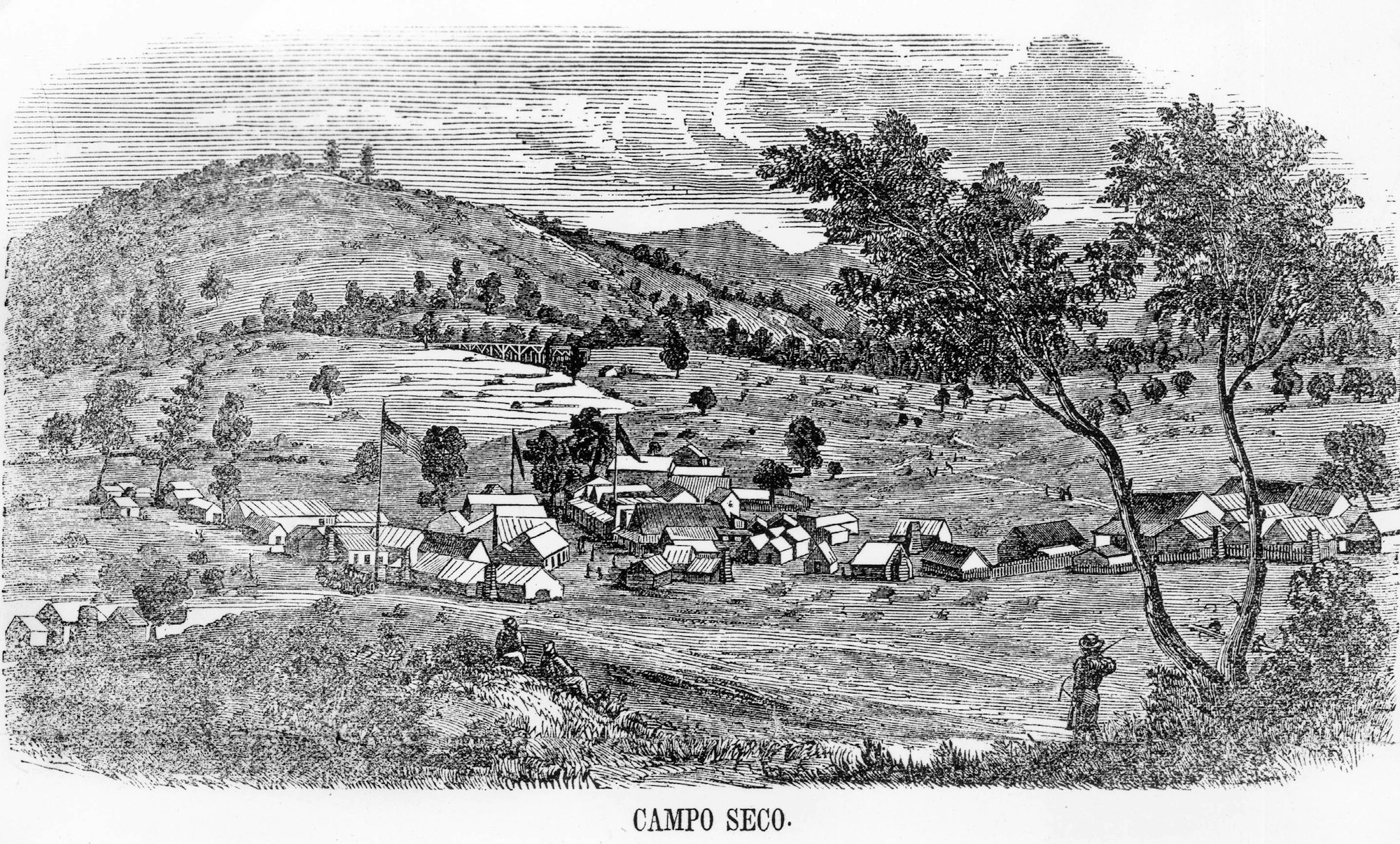

Campo Seco

The community of Campo Seco (Spanish for dry field or camp) was an early placer mining camp that also provided services to the bars along the Mokelumne River (recorded as State Historic Landmark No. 257). The camp was located on Oregon Gulch, which enters into the Mokelumne River at Oregon Bar, and served many of the miners who mined along the numerous bars of the Mokelumne River.

By the winter of 1850, quite a town had sprung up, but lack of water made it necessary for most of the miners to return to the river bars and the town lost half of its population. The camp, however, continued to prosper, and in 1853 and 1854 the mines yielded several large lumps of gold. In December of 1853, the miners of the district adopted a code of mining laws and defined the boundaries of the district; a post office was established the following year, and a school sometime prior to 1855 (Gudde 1875:58, Las Calaveras 1956:2). On August 18, 1854, the town was destroyed by fire and, although many of the merchants and settlers rebuilt, others departed for richer camps.

As was common in the towns near the river bars when the Euro-American miners departed, their place was taken by Chinese and Campo Seco soon developed a large “Chinatown” settlement of stores, a gambling hall, and other amenities. By 1857, however, the population of the town had dwindled to a few hundred miners and store owners. In August of 1859, the town was again almost completely destroyed by fire, but quickly rebuilt. It was described by a reporter the following year:

"The population of Campo Seco in the summer of 1860 is about 300, including 50 Chinese and a sprinkling of Mexicans. The fires last year destroyed nearly the entire town, but most of it has been rebuilt. It contains a few fine gardens, two churches (one used for a school house), two large hotels, one of them stone, owned by Mr. Nye, a number of saloons, and five stores. Mining is dull at present. A branch of the Mokelumne Hill Canal furnishes water for domestic use and irrigation purposes (San Andreas Independent, August 25, 1860)."

In 1859 the ditch of the Mokelumne Hill and Campo Seco Canal and Mining Company provided the camp with water, and the miners returned to work the streams and drainages in the vicinity. During the 1860s some hard-rock (quartz) mines were operating, and in 1862 gold was still being placered on 15 or 20 claims, but the future of the town was not gold, but copper. That year the town boasted a hotel, a restaurant, four stores, two saloons, a brewery, blacksmith shop, livery stable, post office, Wells Fargo office, and two churches; Catholic and Methodist (Gudde 1975:58, Las Calaveras 1956:1, Patera 1987:14).

According to published accounts, two Mexicans and a Chilean miner discovered a rich deposit of copper ore in 1859 in Lancha Plana (Patera 1987:13). Their claim was sold to J.K. Harmon, who operated a successful mine there for many years. In 1862, workers digging a drainage ditch on the north side of Coon Gulch near Campo Seco struck a rich copper lead. Robert Eproson and a syndicate of 14 shareholders developed the lead from which tons of ore were extracted. By 1867 however, the boom was over, occasioned by a glut in the copper market and the cessation of the Civil War and its demand for copper for shell casings (Mace 1993:52).

The townsite was surveyed by H.F. Terry in January of 1870, and a patent issued to James Barclay, County Judge, on September 10, 1872, with nine blocks divided into 67 lots. Boundaries for the lots were determined by prior ownership, the owners having a “claim to possession” of specific parcels. The streets on the Townsite Map were designated Main, College, China, Chilano, and Arkansas Ferry Road. On the eastern end, Main Street merged into the Mokelumne Hill and Campo Seco Turnpike, created by an act of the Legislature of the State of California and a vote of the people at a bond issue (Las Calaveras 1956:3).

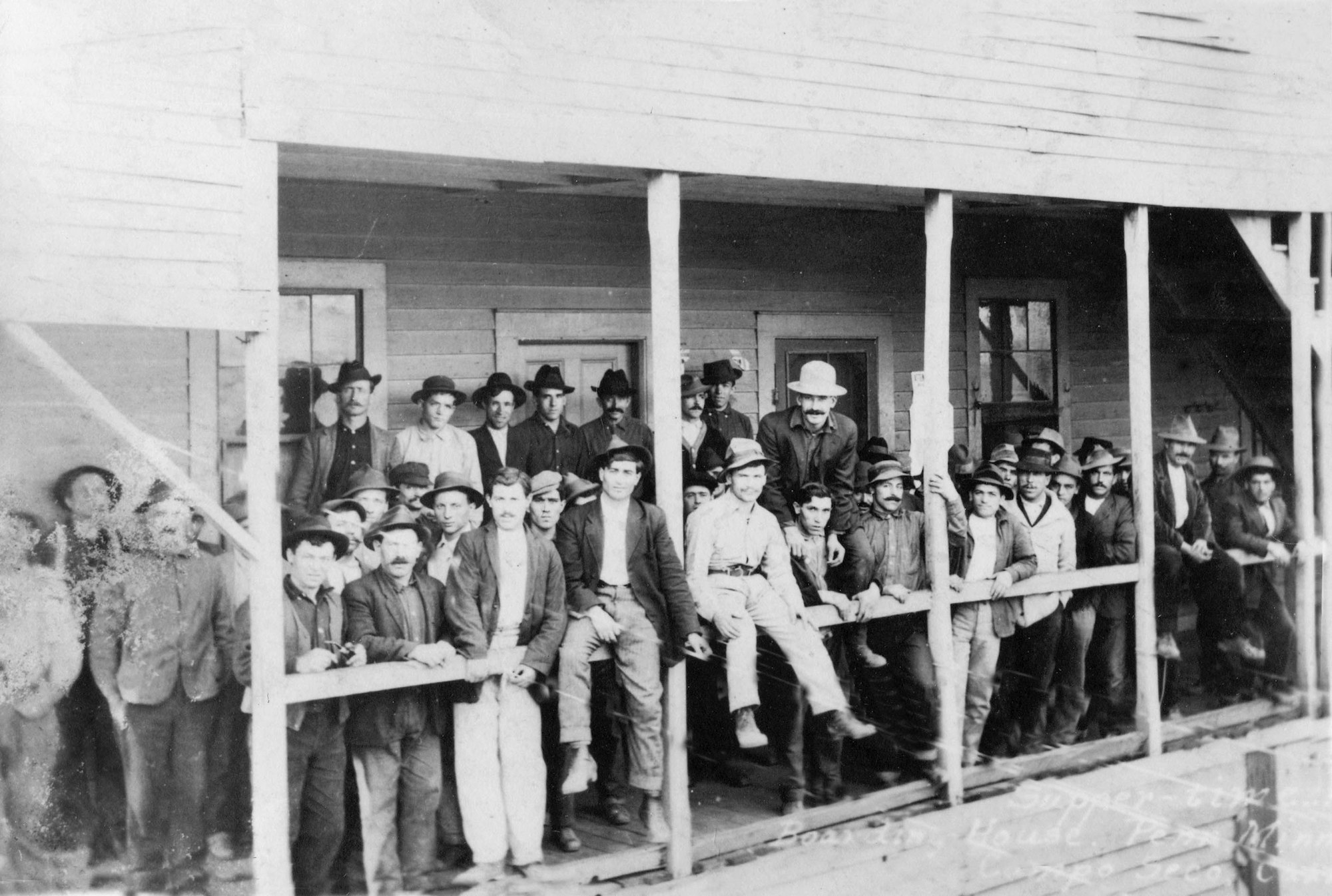

In 1880, the mining of California copper again became a viable business and, in 1883, H.D. Ranlett reopened the Lancha Plana, renaming it the Satellite Mine, selling it three years later to the San Francisco Copper Company. By 1887 many of the mines around Campo Seco were bought up by the Penn Mining Company, whose holdings eventually totaled nearly 1200 acres, including the original Harmon claim, but mining was temporarily discontinued when results proved unsatisfactory. In 1898 the mine again reopened, and the following year the company built a smelter, sunk two deep shafts, constructed a tram to transport ore between the two, and equipped it with a crushing and grinding plant, eight roasting furnaces, and a blast furnace. These improvements ensured a twenty-year period of productivity until the mine’s closure in 1919, responding to the post-World War I economic slump. During this final period of activity, the Penn Mine was the most important copper mine on the West Belt of the Mother Lode (Clark 1962:28, Limbaugh 2004:244-246, Mace 1993:52-53).

Although gold was never again to play the important role it had in the 1850s and 1860s, in 1899 Campo Seco was still described as the center of quartz and drift mines (Gudde 1975:58). Some gold mining was evidently still being carried on at the same time as the copper boom.

The town experienced two more revivals, the first in 1928 when it became host to hundreds of workers during the construction of Pardee Dam. At that time the community boasted four stores, a restaurant, two hotels, a dance hall, a speakeasy, and several moonshining operations. A fire that year, and the completion of the dam and the departure of the workers, caused yet another bust (Mace 1993:53).

The last hurrah for Campo Seco occurred during World War II, when the Penn Mine reopened and was operated on a major scale from 1943-1946 by the Eagle-Shawmut Mining Company, with the ore trucked to their mill near Chinese Camp in Tuolumne County. It continued in operation until 1959, leased by several different corporations (Clark 1962:28-29). Since that time the commercial district of Campo Seco has disappeared, the town served only by the post office and occupied by descendants of early day settlers and a few newcomers (Mace 1993:53).

by Judith Marvin

References

Agostini, J.J. 1904 Official Map of Calaveras County. J.J. Agostini, San Andreas, California.

Barbed Wire Museum, 2006 A Brief History of Barbed Wire. www.barbwiremuseum.com/barbedwirehistory.htm.

Calaveras, County of. var. Deed Books, var. Official Record Books, var. Assessor’s Roll and List Books, var. Water Rights Books, var. Probate Records, 1866, 1888 Great Registers of Voters, var. Townsite Maps, var. Land Patent Maps, 1969 Aerial Survey Maps, September and October 1969. On file, Calaveras County Surveyor, San Andreas. 1977 Aerial Survey Maps, June 22 and 23, 1977. On file, Calaveras County Surveyor, San Andreas.

Child, Bruce, Calaveras County Surveyor. 2006 Personal communication to Judith Marvin of 16 February 2006. Notes on file Foothill Resources, Murphys.

Clark, William B. 1962 Mines and Mineral Resources of Calaveras County, County Report Number 2. California Division of Mines and Geology, San Francisco.

Elliott, W.W. 1885 Calaveras County Illustrated and Described. W.W. Elliott, Oakland, California. Reprinted 1976 by Valley Publishers, Fresno, California.

General Land Office. 1869 Township 4 North, Range 10 East, Plat.

Goddard, George , C.E. 1855? Map of a Survey of the Mokelumne Hill Canal and a Reconnoissance (sic Reconnaissance) of the Adjoining Country. Britton & Rey, San Francisco. On file, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley. Copy on file, Foothill Resources, Ltd., Murphys.

Goffe, Gary, Calaveras Public Utility District, 2006 Personal communication to Judith Marvin of 16 February 2006, Notes on file Foothill Resources, Murphys.

Gudde, Erwin G., Edited by Elisabeth K. Gudde. 1975 California Gold Camps. University of California Press, Berkeley.

Hertzig, John. 2006 Personal communication to Bill Claudino, 23 February 2006.

Hoover, Mildred Brooke, Hero Eugene Rensch, Ethel Grace Rensch, William N. Abeloe, Revised by Douglas E. Kyle. 1990 Historic Spots in California. Stanford University Press, Stanford.

Las Calaveras. 1956 “Campo Seco.” Las Calaveras, Quarterly Bulletin of the Calaveras County Historical Society, Volume 4, Number 2. San Andreas, California.

Limbaugh, Ronald H., and Willard P. Fuller, Jr.

2004 Calaveras Gold, The Impact of Mining on a Mother Lode County. University of Nevada Press, Reno, Nevada.

Lindstrőm, Susan, PhD. 1995 Heritage Resource Inventory, Valley View Specific Plan EIR, 2038-Acre-Parcel Near El Dorado Hills, California, El Dorado, County. A 33% Archaeological Survey. Prepared for Wagstaff and Associates, Berkeley, California.

Mace, O. Henry. 1993 Between the Rivers, A History of Early Calaveras County, California. Gold Country Enterprises, Sutter Creek, California.

Patera, Alan H. 1987 “Campo Seco, Calaveras County.” Western Express, Research Journal of Early Western Mails. No. 151,Vol. XXXVII, No. 4. Quarterly Publication of the Western Cover Society, Unit No. 14- American Philatelic Society, Oakland, California.

Terry, H. F. 1870 The Official Map of Campo Seco. Surveyed January 1870.

United States Federal Census: 1850, 1860, 1870, 1880, 1900, 1910, 1920, 1930.

United States Geological Survey. 1894 Jackson Folio. Scale: 1 to 125,000. Surveyed in 1888. 1962 Valley Springs, Calif. Quadrangle. Scale 1 to:24,000.