Burson

Around 1877, Daniel Smith Burson, a wounded Civil War veteran, and his wife Martha moved from their home in Wyanet, Illinois to Calaveras County where they homesteaded a 160-acre parcel. Burson, a farmer, lived near the summit of a hill he called Pleasant View. With the opportunity presented by the San Joaquin & Sierra Nevada Railroad coming through, Burson transformed his property and recorded the townsite, which he named for himself, on September 22, 1884. But the railroad was not the bonanza he expected and, by 1888, he and Martha moved to the falls of San Antonio Creek near the Big Trees. But the small town named Burson remains.

by Sal Manna, 2010

The True Story of the Founding of Burson

“Burson (Calaveras County)…The name commemorates David S. Burson, a railroad man.” (California Geographic Place Names, 1998) His name was not David and he was not a railroad man. Equally incorrect is the oft-repeated story of the town of Burson failing because of a contentious land negotiation between Daniel Smith Burson and the San Joaquin and Sierra Nevada Railroad–and the railroad thus extending its tracks to Valley Spring and also renaming the depot. Now, more than 120 years since its founding in 1884, exhaustive research into archived County and legal documents as well as contemporary newspaper accounts has uncovered the true story of the founding of Burson. Much of what follows is being revealed for the first time.

In the early 1880s, the land in northwest Calaveras County, just east of the San Joaquin County town of Clements, promised opportunity but little else. South of the copper mines of Campo Seco and gold placer and quartz mines of Paloma and Camanche (what became Burson was first considered Camanche) and north of the farms of Jenny Lind, the area was plagued by very poor, gravelly soil. “Covered with a dense growth of chaparral, giant white oak, live oaks and an occasional pine…mountain streams…nearly all left dry by the last of August” (Valley Review, August 20, 1884), the land was unsuitable for large-scale farming.

Those who persisted and built small ranches and farms were, for the most part, families who had recently emigrated from the Midwest and East as the new transcontinental train line made the trip far less daunting than in past times. Searching for a better life, and with 160 acres offered by the Homestead Act as incentive, they headed west. “There is no other portion of the State that holds out greater or better inducements to the industrious poor man to-day than the foot hills of Calaveras” (Lodi Sentinel, September 27, 1884).

One such family was the Bursons. It is unclear why they settled in Calaveras County, though two other families from Bureau County, Illinois–the Sapps and the Dyers–also arrived around the same time. What is certain is that at least by 1879, Burson, born in Pennsylvania but raised in Illinois, a wounded Union veteran of the Civil War, and his wife Martha (both 48 years old), were claiming a homestead (granted in 1882) on land that today largely runs northwest from the intersection of Highway 12 and Burson Road. Back then, that crossing joined the Stockton Road and various roads heading east to San Andreas, south to Jenny Lind, northeast to Campo Seco and Mokelumne Hill and north to the Mokelumne River. Though Burson could not have known it when he staked his claim, he was located precisely where a railroad was about to come through and change his life forever.

At the time, all roads led to Stockton and its Central Pacific railhead — and nobody outside Stockton seemed happy about that. Farmers in Lodi complained about the high freight rates. Miners in Camanche and Campo Seco had no choice but to incur substantial costs to haul their products. James Sperry, proprietor of the hotel at the rapidly expanding world-renowned Big Trees in eastern Calaveras County, wanted to expand his tourist business by providing an easier trip for visitors than the stage lines that had been operating since the 1860s. The timber interests in that region also craved better access.

Agitation for a narrow gauge railroad that would bypass Stockton and instead connect via steamer directly with the more lucrative market of San Francisco came to a head in late 1881. December meetings among prominent citizens piqued the interest of Frederick Birdsall, who made his money mining silver in the Comstock Lode in Nevada before moving to Sacramento where he was one of the organizers and directors of the Sacramento Bank. Birdsall became the principal investor in the venture which was incorporated as the San Joaquin and Sierra Nevada Railroad on March 28, 1882. The first rail was laid at Brack’s Landing on the Mokelumne River near Woodbridge in April and surveying, grading and construction quickly proceeded. By June the tracks reached Lodi; Lockeford by August, and newly founded Wallace by October, steaming full-speed ahead towards the Big Trees and perhaps even the silver mines of Bodie.

Daniel Burson must have imagined he had stumbled onto a different sort of gold mine than the ‘49ers. In March 1883 he purchased the 160-acre parcel south of his homestead for $3,000, an extraordinarily high sum, from Gottlieb Graupner, a German immigrant. In March of the following year, he granted the railroad a right-of-way through his original property.

The Valley Review (June 4, 1884) described Burson along with neighbor John Peters, who owned the 160 acres to the west, as “intelligent, wide-awake and progressive farmers who will do much to make the place grow in importance and number when it is once fairly begun…just north of the new town site is a beautiful eminence known as ‘Pleasant Hill,’ the home of Mr. Burson, where we found a profusion of roses in bloom…Mr. Burson has set out a row of evergreen and other shade trees on the avenue which leads from the road up through the field to his residence.”

On September 5, 1884, the first train reached Burson, or more accurately, Burson’s, as in “Burson’s place” because the place did not yet have an official name. In fact, the train station was initially christened Hungry Hollow (Calaveras Prospect, September 12, 1884). But on September 22nd, Burson filed with the County an official plat of the Town of Burson, as surveyed by Fred Reed, Chief Engineer of the S.J. & S.N.R.R. From that day onward the area has been called Burson.

The plat shows a town just short of 20 acres, north of the Stockton Road and on the same side as the train depot. Along with 61 lots arranged in five blocks designated A through E, the plan featured a two-acre plaza and six streets, four 80 feet wide and two 60 feet wide. The streets–Brack, Langford, Washburn, Fitzgerald, Peters and Furness–were named by Burson generally with an eye to currying favor among the more powerful. Brack was Jacob Brack, a native of Switzerland who came to California during the Gold Rush. A prominent farmer, he had built a landing on a slough of the Mokelumne River to create a watery avenue to San Francisco and was the prime mover for the creation of the railroad, of which he was vice-president. Langford was B.F. Langford, a native Tennesseean who also arrived during the Gold Rush. One of the most influential men in California, he was State Senator for the area from 1880-1899, and a director of the railroad. (The three locomotives of the railroad were named the “Ernest Birdsall,” after Frederick’s son, the “Ben F. Langford” and the “Jacob Brack.”) Washburn was Samuel Washburn, superintendent of the railroad. J.W. Fitzgerald was a brief business partner of Burson’s. Furness is a mystery, since there was no one by that surname that can be connected to Burson. One possibility is that this was a misspelling referring instead to James Furnish, who perhaps not coincidentally made a loan to Burson the next month.

The plaza in the center of town was planted with trees, mainly 50 olive trees, as well as eucalyptus, cedar, pine and oleander. The necessary water was tapped from a reservoir on a nearby hill, to which the water was piped in by the Mokelumne Ditch Co. According to a recollection written by Lester King March in 1956: “My memory as a very small boy was that it was a very beautiful spot.”

March, a son of long-time town doctor William Bright March who built a house in Burson soon after the railroad pulled in, added that the S.J. & S.N.R.R. then wanted to purchase 10 acres of level land from Burson adjoining their right-of-way on the south for a switching yard. “Mr. Burson set the price above a reasonable value,” wrote March, “and the controversy finally waxed hot, and the railroad people said alright we will build to Valley Spring and also change the name of our station to Helisma which was not a very good sounding name.” March was correct about the latter; for years residents would say with a smile to perplexed outsiders, “Burson is my post office but Hell is my station.”

However, and more importantly, March, who was born three years after Burson was founded, appears to have erred regarding the controversy itself. There is no mention in contemporary documents or newspapers of any such disagreement. Whether the railroad asked to buy property for a switching yard and Burson countered with an exorbitant price is unknown. What is clear is that any such issue had nothing to do with the railroad moving on to Valley Spring (where it arrived in April 1885) since that, and even to the Big Trees and beyond, had been in the company’s plan from the beginning. In addition, the railroad could not have been so terribly upset with Burson himself given that railroad receipts through the remainder of the 1880s show that the enterprise continued to make occasional payments to him of $5 per month for providing water to the station.

As for the name change, the first mention of the station being called Helisma rather than Burson in the annual Officers, Agents & Stations publication of the Southern Pacific (which purchased the San Joaquin & Sierra Nevada Railroad in 1886) is 1892, years after Daniel Burson owned any land in the town or any controversy may have waxed hot. Later accounts propose that problems confusing deliveries to Burson with those to Benson, AZ, was the rationale for the change. The source for the ungainly name of Helisma remains unknown.

Blaming Burson for a poor business decision that stymied the town’s development is ill placed for another reason as well. If offered money from the railroad, he surely would have taken it without much of a hard bargain–because little more than a year after founding Burson, its namesake went bankrupt.

Burson was a man of modest means, receiving what was likely a very small Civil War pension to supplement his limited farming efforts. In 1882, according to property tax records, Burson owned his land, house, one plow, one wagon, three colts, two cows, one calf, one dog, poultry, one harness, firearms, furniture, a horse, and, extravagantly, a thoroughbred worth $300. Per 1884’s assessment, though he owns much of the same, he has now mortgaged his land to John Storey, a successful Irish-born miner dubbed “the Bonanza King of Camanche”; to Graupner, for the additional land earlier purchased, and to Hattie Sterling, a German-born widow who was a frequent money-lender to area residents. Burson, as did a few others, staked his future on the railroad ushering in an economic boom for the entire county.

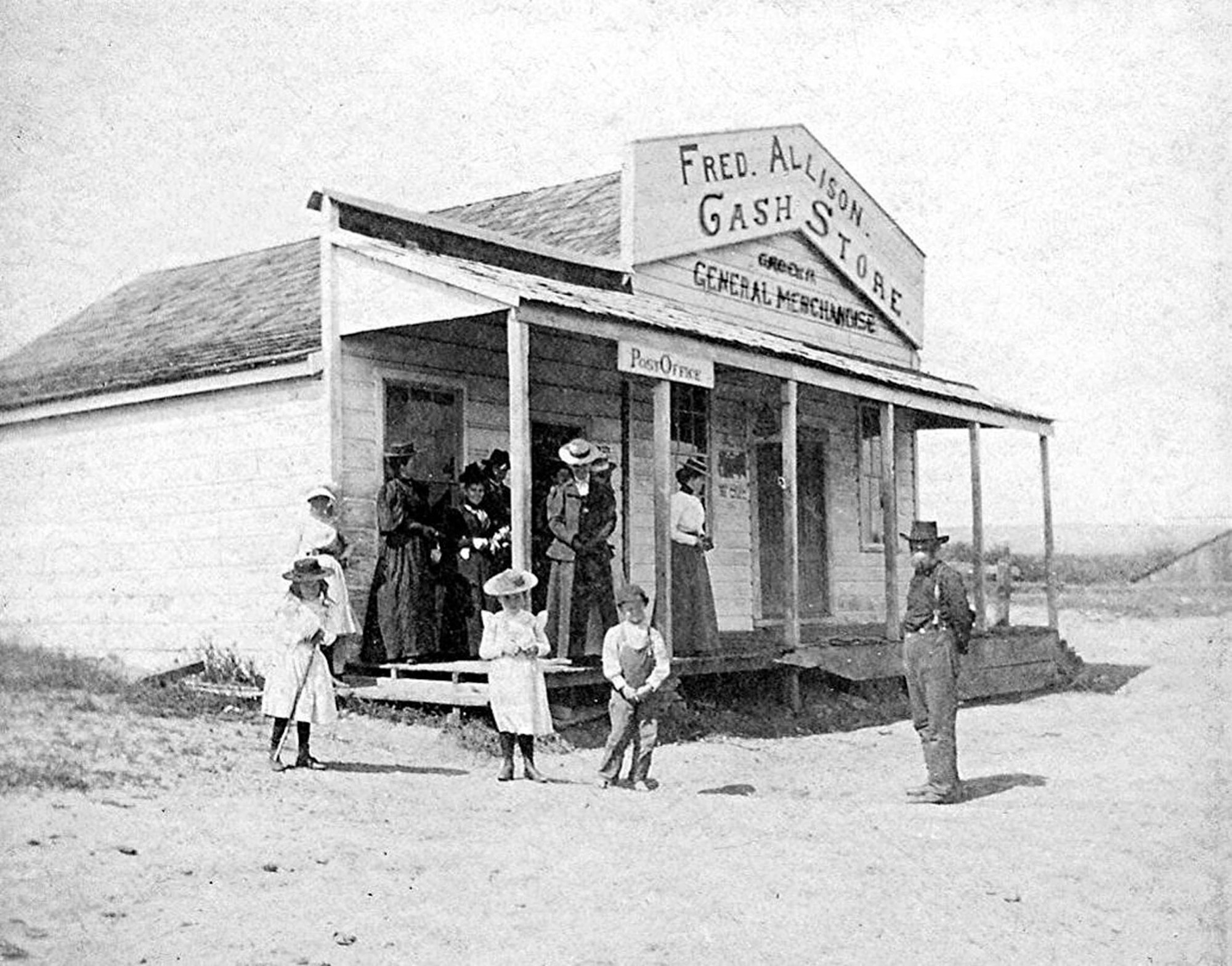

The small town quickly boasted a post office, stores, dance hall, saloons, livery stables and numerous residences. Daniel Burson sold lots to Jay Conklin, a brickmason from Ohio; to Ed Caldwell, a miner turned saloonkeeper from Canada; Marcus Lafayette Cook, a Tennessee-born farmer who opened a store and became Burson’s first postmaster, and storekeepers William Cook (M.L.’s son) and Iowa’s Warren Lamb, plus acreage north of the site to Fred Walter, a German-born blacksmith who became one of the town’s solid citizens, and a postmaster, for many years. But despite Burson’s efforts, and expense, the vast majority of the lots went unsold.

In mid-1884, the Valley Review touted that “this new railroad will prove a great blessing to these people so long shut off from the commerce and manufacturies of the world, and as capital is introduced, the resources of the valley and mines better developed, towns will spring up, and all the advantages enjoyed by the denizens of more favored localities will be meted out to those brave pioneers who have toiled and reared their families on their foot-hill farms contented with their surroundings nor ambitious to enter the arena of fortune to struggle for wealth, honors and fame, though surely the first of these will come without the seeking.”

In 1884, the narrow gauge carried 21,512 passengers and more than 19,000 tons of freight. The following year, it carried 19,908 passengers and 12,234 tons of freight. In 1886, it carried 15,706 passengers and 13,000 tons of freight. Also, per revenues and debits, the railroad was in the black. The S.J. & S.N.R.R., contrary to popular belief, was not a failure. Yet the cost of its building, and the interest expense on its bonds, weighed heavily on investors. The San Joaquin Historian writes that “the crushing blow came with the death of its chief financier and president, Fredrick Birdsall.” That claim is erroneous, however, since Birdsall passed away years later on April 23, 1900.

Nevertheless, the railroad was certainly not as explosively successful as everyone had hoped and the growth of Calaveras County that it was supposed to spark never materialized. That the line was not extended beyond Valley Spring (other than the 1925 expansion to the Calaveras Cement Co. in San Andreas) spelled the end of any potentially major commercial advance for the county for many decades. One can only imagine what Calaveras County would be like today if the railroad had indeed stretched to the Big Trees.

So what went wrong with Burson’s particular dream of a thriving, prosperous new town? Burson “flourished while serving as the terminus of the railroad, with freight bound for the mines being unloaded there for transfer onto large freight wagons” (San Joaquin Historian, July-September 1975). But within a matter of only seven swift months from its founding, Burson was simply passed on by. Valley Spring became the new terminus (and later became Valley Springs). Daniel Burson had known that his hamlet would never remain the end of the line. Time was of the essence to draw either a substantial population or significant added resources before the railroad moved on. Neither occurred, for a myriad of reasons, most beyond his control–from a national economic recession to better prospects for money and people elsewhere in California to the lack of a powerful benefactor.

Meanwhile, Daniel Burson was deeply in debt. According to his bankruptcy proceedings, he owed money for everything from groceries and blacksmithing to pipe and powder, a sum of more than $7,000. His assets at the time of his filing as an insolvent debtor were one wagon, two horses, one harness, and household furniture, totaling $295. He claimed to own no real estate because a month earlier, in October 1885, he cleverly deeded all 320 acres of his land to his wife. With that apparently effective maneuver, they continued to live on the property, with Martha as the legal, tax-paying owner. Daniel was still considered an upstanding member of the community, serving on juries and mentioned positively in newspapers. In June 1887, the Calaveras Prospect noted that he had a strawberry patch containing 5,000 plants and that he had sold 1,200 pounds of the fruit. However, two of those who held mortgages, including Sterling, were not so easily put off. They sued the Bursons in court and won. By 1888, the Bursons were forced to surrender all of their land to the note holders. They soon moved to the falls of San Antonio Creek near the Big Trees, where Martha Burson claimed yet another 160-acre homestead.

Burson the town did not disappear with the relocation of the Bursons. In the 1890s, for example, Burson was the area’s center for Memorial Day activities thanks to residents who had erected the county’s first post of the Grand Army of the Republic, the organization for Union Civil War veterans. Individual Burson businesses and residents have continued to prosper through the years. Gold Country travelogues notwithstanding, Burson has never been a ghost town.

Daniel Burson died on November 24, 1907, at the age of 78. Less than three years later, Martha passed away at age 80. Both are buried at the Harmony Grove Cemetery in Lockeford, with Daniel’s final resting place marked by a Civil War headstone. His obituary in the Calaveras Prospect read: “D.A. Burson after whom the town of Burson was named…was a native of Iowa…He came to this county in the early days, and at the time of the building of the Lodi and Valley Spring railroad, he started the town of Burson as a public resort, but was not successful.” In his own obituary, his name is incorrect (D.A. instead of D.S.) and his birthplace is incorrect (Iowa instead of Pennsylvania).

The newspaper does accurately cite that his dream did not come to fruition. Yet, 120-plus years later, there remains a town named after him, a road running through it that also bears his name, and citizens proud to live in a small Calaveras County town called Burson.

By Sal Manna; first published in “Las Calaveras,” July 2005