Middle Bar

The history of Middle Bar is inextricably linked to several features of its past -- mining, its location as a river crossing, commerce, and agriculture. Each of these, in turn, helped to spport the community and provide livelihood for its occupants.

Early Explorations

The earliest Euro-American visitors to the Middle Bar area, whose travels are left unrecorded, were most probably early explorers following paths long used by indigenous peoples. James D. Martin, in company with a party of seven other men, passed through the Ione Valley on his way to the Mokelumne River in the summer of 1848 (Mason 1881). Colonel Jonathan Stevenson and about 100 of his men also visited the Mokelumne in 1848, mining on the river near Mokelumne Hill (Mason 1881; Mace 2002). In 1849 Bayard Taylor visited Middle Bar as did August Taylor, the latter noting that Don Andreas Pico, brother of the former Mexican Governor Pio Pico, was mining at Middle Bar with a company of men (Cenotto 1988).

Mining

Mining endeavors on the Mokelumne River began as early as 1848. Miners found the river gravels profitable and by 1850 a considerable settlement was established at Middle Bar. Advertisements in a March 1850 issue of the Stockton Times carried advertisements for a large dry goods store and a ferry crossing (Cenotto 1988). In December of that same year a reporter for the New York Herald visited the camp and described the settlement as being worthy of note, quite extensive, and the location of a large trading center with the population including all ethnic groups, numbers varying at times between five to eight hundred people. He also noted several companies were spending weeks digging canals and building dams to turn the river for mining purposes (NY Herald). Another chronicler visiting the camp that year described it as “…one of the most frequented mining places…the middle-bar of the Maqualome…” (Cenotto 1988).

By the 1860s placer mining ceased, the gulches being thoroughly washed out. Although the gravels were later re-worked by Chinese for a short time, interests turned to hard rock mining, with several ore mills located near the river (Sargent 1927).

The 1866 Official Map of Amador County notes several hard rock claims in the immediate vicinity of Middle Bar, two of these up Spanish Gulch, and Marlette’s Mine and Mill a short distance downstream of the Middle Bar bridge. Marlette arrived at Middle Bar in 1849, noted as being one of the earliest miners to take up hard rock mining in Amador County (Sargent 1927). In 1859, a deed recorded the purchase of the mill by John B. Marlette & Co. from Jabez C. Arnold. In addition to the mill, Marlette purchased two mining claims and a ditch delivering water to the mill (Amador County Archives File No. 7815.7). Marlette continued to work in the mining industry but by 1870 he had sold his property and mining interests to the A.J. Sargent family. In 1880 the census lists him as a miner living with the McKinney family (Chavez et al 1984; U.S. Federal Census 1880).

Other mines worked in the vicinity of Middle Bar were the Farrell, Hardenburg, Julia, Little Sargent, Mammoth, McKinney, Meehan, Middle Bar, Sargent, St. Julien, and Valapariso (Carlson and Clark 1954). Many of these ceased operations during WWI. There was a lode mining revival at Middle Bar in the 1930s but this was short-lived (Hoover, Rensch and Rensch 1937). Another startup of activities took place after WWII but again was limited. The last mines to be worked were the Mammoth and the McKinney and Crannis claim (Sargent 1927; Carlson and Clark 1954).

Transportation

As early as the 1850s, Middle Bar found its place as an important crossing over the Mokelumne River, accommodating travelers between mining camps to the north and south. The Stockton Record, in March of that year, carried an advertisement for Grambis and Page’s Ferry at Middle Bar. The ad stated the public would find “at the above ferry every accommodation for the passage of freight and mules over the river.” Prior to this a traveler would have had to travel west to Lancha Plana to cross the river. In October of that same year citizens filed a petition for a public road extending from Middle Bar north to Amador City and mining camps at Rancheria Creek, and a branch on the south side of the river to Double Springs (Cenotto 1988).

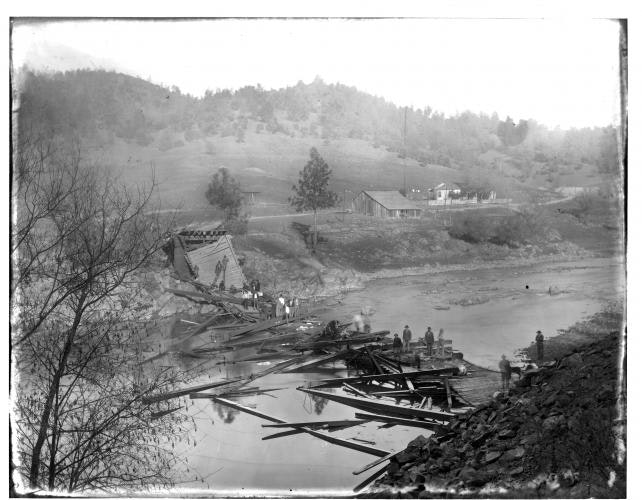

In 1851, the ferry was replaced by the first toll bridge across the river, built by J.W. McKinney and Abraham Houghtaling. By December of 1851 a stage began regular runs between Mokelumne Hill and Sacramento via Middle Bar. The bridge stood for only one year. Heavy rains and a swollen river washed it away in 1852, leaving McKinney and Houghtaling to ferry travelers and goods across the river until a new bridge was constructed later that same year. This bridge stood for about 10 years until the winter of 1861-62 when it was washed out by another winter of heavy rain (Cenotto 1988). With the wane in placer mining, the population at Middle Bar declined and the need for a new bridge was diminished. Upriver, a bridge built at Big Bar (modern Highway 49 crossing) was also washed away in January of 1862, but was soon rebuilt leaving Middle Bar as a secondary route.

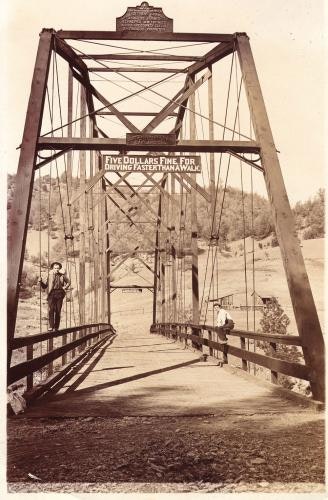

For nearly 30 years the Middle Bar crossing was without a bridge. It wasn’t until 1895 when the prosperous Gwin mine in Calaveras County, downriver from Middle Bar, inspired the building of a new span across the river. In 1911 the bridge again collapsed, this time under the weight of too many cattle. In autumn of the following year the Clinton Iron Works constructed a new bridge (Chavez et al 1984). This bridge, which spans the river today, was paved in 1941 (Sutter Creek News 1941).

Settlement

The first Euro-Americans to settle at Middle Bar were miners, most staying for only a short time and leaving after the Gold Rush was over. Others remained, turning their interests to merchandising and agriculture. Several families arrived at Middle Bar in the 1850s and 60s and stayed for several decades. These families included the A.J. Sargent family, the Bales, Boitanos, Garaventas, and Sanguinettis (Chavez et al 1984). Although by 1850 the population of the settlement reached at least 500 persons, just 30 years later it had diminished considerably (Chavez et al 1984). In 1880 when J.D. Mason compiled his history of Amador County, he noted that only a few old cabins remained of what was once a bustling mining camp (Mason 1881). Despite the miners taking their leave, Middle Bar continued as a viable community into the 20th Century.

The A.J. Sargent family came to Amador County in 1854 and shortly thereafter built a cabin and settled at Middle Bar (Sargent 1927). By 1860 Sargent was engaged in mining and later added carpentry to his livelihood (U.S. Federal Census 1860, 1870). Sargent worked several mining claims for a number of years including the Marlette claim that he purchased in the 1860s. By 1880 he was also engaged in agriculture (Sargent 1927). Succeeding generations occupied the Sargent homestead into the early part of the 20th century.

The Peter Bales family arrived at Middle Bar from France in the 1860s. Bales engaged in both mining and farming. He worked several claims along the river and planted vineyards with cuttings he brought from France. By the turn of the century Bales had sold out to the Boitano and Sanguinetti families. These families also engaged in both mining and agriculture. As late as 1910, the census listed them as farmers (Chavez et al 1984). The Garavanta family settled near Middle Bar on the Calaveras side of the river and stayed for at least 30 years. After working a small quartz claim for awhile they operated a small farm. In 1895 they were assessed for taxes on livestock, a vineyard, fruit trees, and a vegetable garden (Chavez et al 1984). John Garavanta remained on the ranch into the 1940s.

Other settlers at Middle Bar engaged in merchandising for their livelihood. One of the earliest settlers who supplied goods to the settlement was Abe McKinney. In the early 1850s he was in the employ of Tom Bennett, who operated a general merchandise store on the Calaveras side of the river. As discussed above, throughout the 1850s he held interest in the toll bridge and operated a ferry across the river in partnership with Abraham Houghtaling. By 1860, McKinney was operating his own inn and small store on the Amador side of the river. He is also noted as having a small agricultural operation, which included chickens and two gardens. McKinney resided in Middle Bar with his wife and children until his death on June 7, 1896 (Amador Republican 1896).

Settlement at Middle Bar waned after the Gwinn Mine closed in 1908; in 1910 the Post Office was closed. However, in 1911 several families still resided on both sides of the river. After the bridge collapsed that year, residents constructed a foot bridge across the river so that children on the Calaveras side of the river could cross to attend school (Amador Ledger Dispatch 1911). Soon after that, the Middle Bar settlement was abandoned to cattle grazing.

Middle Bar Ditch

Archival research revealed that the Middle Bar ditch, located on the north side of the Mokelumne River, was most likely used in association with mining operations that began in the 1850s. The earliest mention of a ditch in this vicinity is referred to in a note written from Constantine Johns to James Masterson on Dec. 6, 1857, wherein Johns requests Masterson to “come down and do that ditch business for us”. Later correspondence between Johns and Masterson, written in 1858, requests that Masterson survey “our ditch” for a distance of about 2 ½ miles. One year later another transaction was recorded which references a ditch at Middle Bar. In 1859 a deed recorded the sale of a ditch, two quartz lodes and a quartz mill at this location, transferring them from Jabez C. Arnold to John B. Marlette and others, operating under the name of Marlette and Company. The property was described as follows:

"…a quartz lode situated on the northerly side of the Mokelumne River….one fourth of a mile below Middle Bar Bridge and upon Pigot’s Flat…..also that quartz lode situated on the northerly side of the Mokelumne River lying about one fourth of a mile above Middle Bar Bridge…also that quartz mill erected on the northerly bank of said Mokelumne River…near that quartz lode firstly above described together with that ditch constructed for the purpose of conveying water to furnish power to drive machinery in said mill and leading from said river at a point above said mill along down the northerly bank of said river to said mill…."

Marlette continued to work at mining for some years; however, by 1870 he had sold his property to A.J. Sargent (Chavez et al, 1984). It is not known how long Sargent worked the mining interests he purchased from Marlette but the Sargent family resided at Middle Bar into the early part of the 20th Century. The ditch recorded during this study passes directly through the property owned by A.J. Sargent.

by Deborah Cook and Julia Costello, 2002, Cultural Resource Study of Middle Bar for EBMUD.

References

Amador Dispatch. 1911 Newspaper article. February 24, 1911. Construct Tramway Across Mokelumne; Middle Bar Citizens Forestall Plan of Supervisors for Footbridge. Jackson, California.

Amador Republican. 1896 Newspaper article. June 12, 1896. Death of Abe McKinney. Jackson, California.

Calaveras County Historical Society. 1954 Las Calaveras, Volume 2, Number 5. Bridges Over the Mokelumne River. San Andreas, California.

Carlson, Denton W. and William B. Clark. 1954 Mines and Mineral Resources of Amador County, California. California Journal of Mines and Geology, Volume 50, Number 1. State of California Department of Natural Resources, Division of Mines, San Francisco.

Cenotto, Larry. 1988 Logan’s Alley; Amador County Yesterdays in Pictures and Prose, Volume 1. Cenotto Publications, Jackson, California.

Chavez, David, Laurence H. Shoup, James Gary Maniery, Mary L. Maniery, and Vance G. Bente. 1984 Cultural Resources Evaluations for the Upper Mokelumne River Hydroelctric Projects, Calaveras and Amador Counties, California; Middle Bar Project Inventory (FERC No. 4289). Prepared by David Chavez & Associates, Mill Valley, Ca. for EDAW, Inc., San Francisco, Ca.

Hoover, Mildred Brooke, Hero Eugene Rensch, and Ethel Grace Rensch. 1958 Historic Spots in California. Stanford University Press, Stanford, California.

Mace, O. Henry. 2002 Between the Rivers; A History of Early Calaveras County, California. Paul Groh Press, Murphys, California.

Mason, J.D. 1881 History of Amador County California with Illustration and Biographical Sketches of it Prominent Men and Pioneers. Thompson and West, Oakland.

Sargent, Mrs. J.L., Editor. 1927 Amador County History. Amador County Federation of Women’s Clubs. Printed at the Amador Ledger, Jackson, Ca.

Smith, J. A. 1954 Middle Bar Ferry and Bridges. Las Calaveras. Vol. 3(1).