Calaveras County

The history of Calaveras County is much like that of other counties in the California Mother Lode. Hoards of miners came; water systems were developed; settlements grew up around the more successful and environmentally rich mining areas; transportation networks developed, first as trails and then as wagon roads; farms, orchards, and truck gardens sprang up; saloons and fandango halls, along with boarding houses provided entertainment, bed, bath, and sustenance; and the bare bones of civilization in the form of government, newspapers, and social lodges developed.

The first recorded visit by a European to the area now known as Calaveras County was made in October 1806, when Gabriel Moraga, with his diarist and chaplain, Padre Pedro Muñoz, visited the Stanislaus River area on their search for potential inland mission sites. During a subsequent visit in 1808, the Moraga expedition named the major rivers in the region, calling the Stanislaus “Rio de Nuestra Senora de Guadalupe.”

General Mariano Vallejo was in the area in 1829 with a party in search of the escaped mission Indian, Chief Estanislao, for whom the Stanislaus River may have been named. It is believed that Estanislao received his Christian name when baptized, in honor of one of the Polish saints names “Stanislas.” The river became known as Rio Estanislao, and was anglicized by John C. Frémont in 1844. On the opposite side of the county, the Mokelumne River was given the name of the Indian group who resided there.

Moraga and Vallejo were soon followed by Jedediah Smith, Joseph Walker, John Frémont, and by the French trappers working for the Hudsons Bay Company and headquartered at French Camp near Stockton. The Bidwell-Bartleson Party, an emigrant group, traveled through the area in 1841, followed by others of their ilk. There is little information about any historic settlements from this early era, however, or remains of any settlements of Sonoran miners. Historic activity began in earnest soon after Marshall’s discovery of gold on the American River in January of 1848; an event that forever changed the face of Calaveras County’s physical and cultural landscape.

The name of the county was derived from the Calaveras River which courses through its northern half, reputedly named Rio de los Calaveras (“River of Skulls”) by members of the 1806 Moraga expedition who claimed to have discovered the skulls of Native Americans along its banks. Although the area was visited by successive waves of trappers and traders over the ensuing years, and pertinent evidence indicated that the area was mined for gold by people of Hispanic origin, it wasn’t until Americans discovered gold on the American River in January of 1848 that the local area was visited by any appreciable numbers of Euro-Americans.

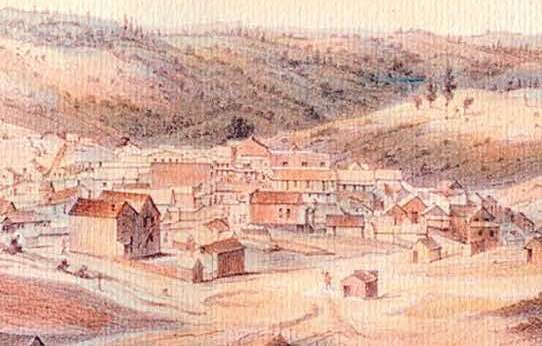

When California was admitted to the Union in 1850, Calaveras, which then included present Amador County and part of Alpine County, was one of its original 27 counties. It has had four county seats, the first named was at “Double Springs or Pleasant Valley,” which simply became Double Springs, where the first county officers were elected in April of 1850. In 1851, however, both Jackson and Mokelumne Hill petitioned for an election to move the county seat, and after much wrangling, it was established at Jackson. By 1852, with Mokelumne Hill much larger than Jackson, it was again moved. There it remained until, with the decline of gold production in the Mokelumne Hill area in the 1860s, and due to its distance from the southern half of the county, voters selected San Andreas as the new county seat. In 1867, a new courthouse and jail were completed, and with the move, county officers, attorneys, and many professional people relocated to San Andreas, changing the demographics of the county forever.

As the century progressed, some Gold Rush settlements became villages and then towns, while others disappeared. Churches and schools were established, and community and fraternal organizations flourished. Neat frame houses and brick and stone commercial buildings replaced the tent cities of the miners. Hotels and inns, general merchandise stores, tin and carpenter shops, boot and shoe shops, liveries, and the ubiquitous saloons lined the main streets.