Murphys

The history of Murphys is typical of many other towns in the California foothills, with their booms and busts, colorful characters, and almost century-long dependence on mining. The prosperity of the communities was first based upon the rich placer gold found in Murphys/Angels Creek and its tributaries and their drainages. It wasn’t long, however, before the community had become a trading center for the neighboring mines.

According to most accounts, the country around Murphys was first mined in July 1848 by John and Daniel Murphy, two brothers from Santa Clara County, who came to the area with a company of miners that included Henry Angel and James Carson. The brothers set up a trading post, and were very successful in getting the Indians to mine for them; John even “married” a Miwok named Pokela, whose father was a local “chief.” By the time he left the camp in December 1849 to return home, John Murphy reputedly had more gold than any other man on the Pacific Coast.

Large amounts of gold were extracted (statistics vary so widely as to be impossible to accurately determine how much) during the early period of activity from 1848 to 1850. By 1850s, however, the mines were overcrowded and unsuccessful. Seeing a need for water to operate the mines, the Union Water Company was organized and by January 1853, a series of flumes and ditches had brought water 15 miles from the Stanislaus River to Murphys. Mining again prospered and ditches were constructed to all mining areas around the flat. The next ten years were the greatest in the history of placer mining for Murphys.

In addition to the Union Water Company ditch, there were two other engineering feats of magnitude. The Deep Cut, a ditch dug and blasted out of bedrock 4,000 feet long and 37 feet deep, was completed in 1857. Located south of town, its purpose was to drain the flat and mines so mining could continue during the wet months. The other feat was the construction of a suspension flume across the lower end of the canyon to carry water from the North Ditch of the Union Water Company to the Central Hill Mine. The north tower was 94 feet high and the south was 124 feet; the flume stretched 740 feet from tower to tower. The box carried 50 inches of water and was completed in November 1857. It blew down in a storm shortly thereafter.

Three major placer mining areas were located around Murphys: Owlsberg or Owlsborough, Algiers, and Murphys Gulch. The rich placer gold in the stream beds was soon depleted and it was not long before the miners traced the source higher up on the hillsides. The two major mines in the area were the Central Hill, a tertiary gravel mine located on the Central Hill Channel south of Murphys (present sewer ponds on Algiers Street), and the Oro y Plata, which included the Red Wing, Blue Wing, Payrock, and Sulphuret group, on the ridge north of town.

As in other areas in Calaveras County, and the Mother Lode region in general, the early days of mining characterized by individual miners working small claims gave way to the formation of companies of miners as the easy placer gold was depleted. Many disillusioned men returned to “the States,” but others stayed. Although many of those who remained continued to mine, many others turned to commerce and agriculture for a living. They sent for families, or returned east to marry and brought their brides west, and the town was quickly settled. Industries and commercial enterprises were established, and the community took on an aura of permanence and well-being.

The first sawmill in town was constructed by the Union Water Company to provide lumber for its flumes. Soon many other mills were in operation to provide timbers for the mines, and lumber for houses and buildings. Sawmills in Murphys included the Hanford/Dickenson/Kimball and Cutting Mill, the Sleeper/Dunbar Mill, and the Manuel Lumber Yard.

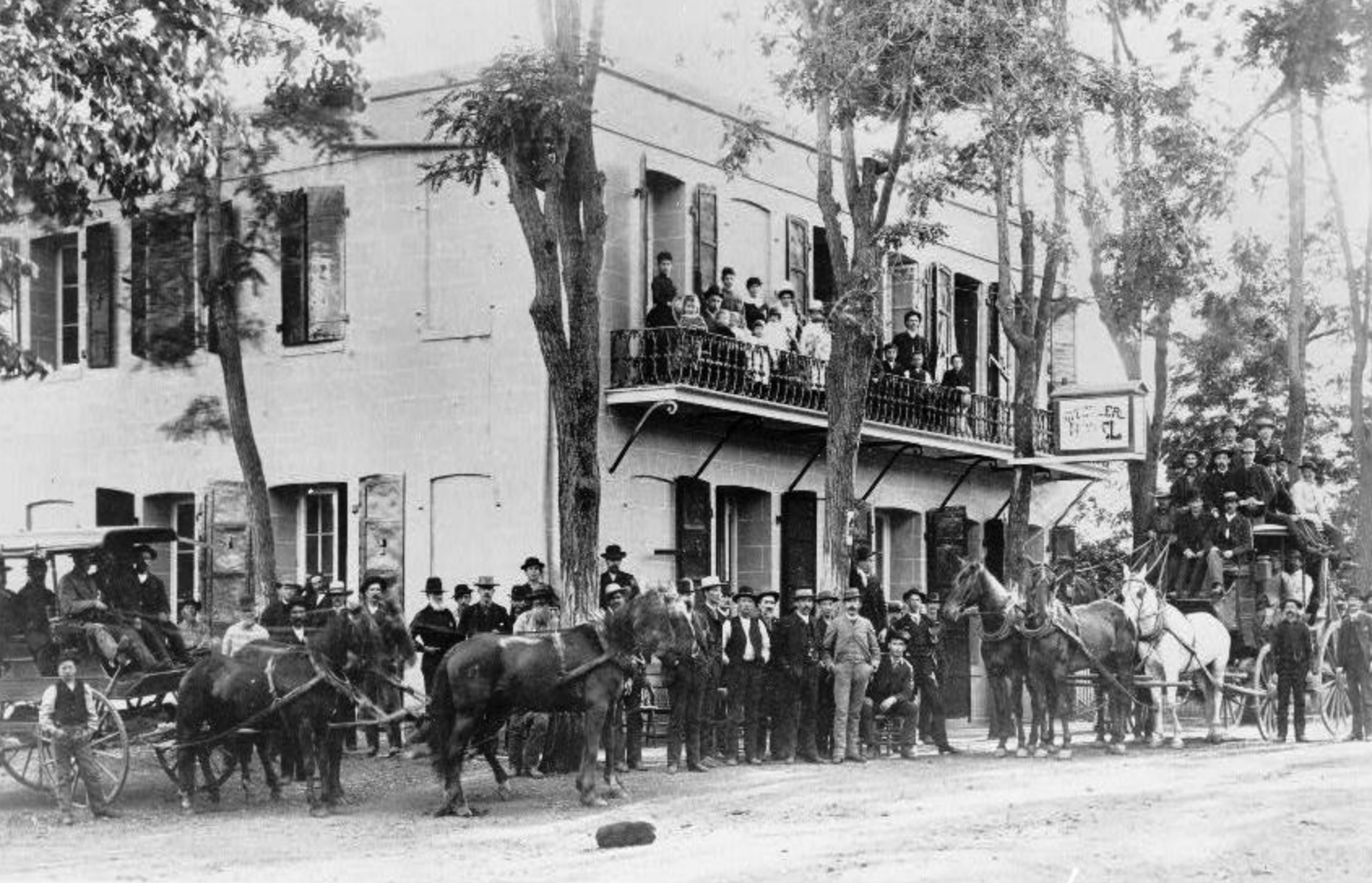

By the early 1850s, Main Street was lined with one and two-story commercial buildings, occupied by hotels, saloons, tinsmiths, carpenters, bakers, general merchandise establishments, liveries and stables.

A fire in 1853, starting in "an immigrants' cottage" was contained by demolishing adjacent buildings to block the spread of fire. The danger was noted, however, and some new constructions were made of stone. The Traver Store (Murphys Museum) was constructed in 1854, and the Murphys Hotel in 1856. It wasn’t until another major fire in 1859, however, that most of the existing brick and stone buildings were constructed; this time the townsfolk opted for permanence. Other fires consumed yet more buildings, and the structures remaining today are comprised of those buildings that survived the vicissitudes of time and fire.

Religion came early to Murphys. The first Catholic church was constructed in 1855 and the first Protestant church in 1853. These were later replaced by the brick St. Patrick’s Catholic Church dedicated by Archbishop Alemany in 1861, and the white frame Union Congregational Church dedicated in 1895 on the site of the former Union Church.

Murphys also had its share of fraternal organizations. The Masons, organized in Murphys in 1852, constructed their present lodge building on Church Street in 1902. The Independent Order of Odd Fellows, organized in 1859, constructed their Main Street lodge in 1902 also. In 1882, the Independent Order of Good Templars, a temperance organization, constructed a lodge building on Main Street, but it was later sold to the Native Sons of the Golden West, an organization not known for its temperance. Formed during the Gold Rush years, E Clampus Vitus has its “Wall of Comparative Ovations” on the west elevation of the Thompson Building on Main Street.

During the American Civil War, in 1861, the Calaveras Light Guards were organized in Murphys. The Guards first met in Crispin’s Salon on Main Street, but later built Armory Hall on Armory Hill north of town; it burned in 1893.

Murphys already boasted three private schools by 1855 when the first public school was established on the site of the present Masonic Hall. In 1860 the school district constructed the frame two-room “Pine Tree College,” now listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

The architecture of Murphys today is made up of a homogeneous blend of wood, brick, and stone buildings dating from the early 1850s to the present. It is an interesting mix of commercial and residential buildings that was characteristic of the latter half of the nineteenth century. A great many historic buildings remain in the core of the town, primarily along Main, Church, Jones, and Scott streets, and Sheep Ranch Road.

Many of the historic commercial buildings were built of stone or of brick facades with stone rubble walls. They all have characteristic Neoclassical proportions: pediment roof, raking cornice, and dentil cornices. The wood commercial buildings are of frame construction with horizontal board siding and gable roofs. Some are Italianate Commercial dating from the 1860s, while those dating from the 1880s through the early 1900s have traditional western style false fronts, recessed doorways, and storefront windows.

The early residences in Murphys were of frame construction; vernacular examples of higher architectural styles found in the Eastern U.S. They included simple Neoclassical, Gothic Revival, and Italianate buildings with horizontal board siding, gable or hipped roofs, and stone foundations. Fenestration consisted of wood frame windows, 6/6 lights, double-hung. Doors were centrally located on the primary facades and were of frame construction with four recessed panels. Most of the residences had porches, full-width across the façade, and often wrapping around one or both side elevations. Beginning in the last decade of the nineteenth century and continuing into the early years of the twentieth, simple one- and two-story Queen Anne residences, with their asymmetrical facades, decorative shingles, and spindlework, began to make their appearance.

Following the decline of placer mining in the Mother Lode after 1860, ranching became more important to the foothill economy. Local farming never developed much beyond a subsistence level and gradually gave way to livestock operations. As the mining economy declined, however, farming gained importance as a family enterprise which helped to establish more permanence and stability in the society. Truck gardens were established, mostly by Italians, and produce was delivered to the towns and outlying communities by wagon. Almost every family planted vegetable gardens and orchards, especially apples and other fruits, while others planted grapes and developed wineries.

Many families in the Murphys area raised at least some livestock, including milk cows, stock cattle, hogs, sheep, goats, and chickens for family consumption. A few, however, made their livelihood by establishing cattle and sheep ranches, selling to butcher shops, and later driving their stock to the railhead at Milton for transportation to distant markets. Barns were also associated with many of the original residences in the community, as families kept a dairy cow or two, some sheep, a hog, and chickens. Orchards and vines were planted, and vegetable gardens established, enabling most families to be relatively self-sufficient.

Transhumance, the upland grazing of cattle, sheep, and goats, was an important historical land use. As early as 1850, there were accounts of stock grazing in the high country, where the ranchers from the foothills drove their stock every June or July so that the animals could partake of the verdant mountain pastures. This cycle was extremely important, as the green grass of the lower elevations would have been eaten and the stock ponds would be dry by mid-summer. By the mid-1860s, virtually every lake, meadow, or other open area had been appropriated by stockmen, especially after the advent of the 1862 Homestead Act. This pattern of high country stock grazing has continued to the present, although in greatly reduced numbers.

It was mining, however, that provided the impetus for the development of the logging industry in Calaveras County. Millions of board feet of lumber were needed for the miles of flumes required to convey the waters from the rivers and streams to the placer mining areas, and many more were required for timbering the underground mines. As the towns developed, lumber was also needed for the construction of the houses and commercial enterprises.

Equally as important as gold mining to the later development of Murphys were the nearby “Natural Wonders” of the Calaveras Big Trees, caverns, and other scenic attractions. Murphys became the gateway and stopping place for those countless travelers who came to the area to observe those wonders. Among the recorded visitors were the illustrious writers Bret Harte and Mark Twain, who used Murphys as the locale for some of their stories; James Hutchings, who wrote glowing accounts in several editions of his Hutchings’ California Magazine in the 1850s and 1860s; and well-known personages such as Black Bart, Horatio Alger, Ulysses S. Grant, Henry Ward Beecher, John Bidwell, and others too numerous to mention.

In 1852, a hunter for the Union Water Company “discovered” the Calaveras Big Trees. Although they had been noticed by emigrants over the route including John Bidwell in 1841 and by several others in 1849, it was Augustus T. Dowd who received credit for their discovery. As noted by chronicler James Mason Hutchings in 1859:

"Murphys Camp, which until then had been known as an obscure, though excellent, mining district, was lifted into notoriety by its proximity to, and the starting point for, the Big Tree Grove, and consequently was the center of considerable attraction to visitors."

As Murphys was located in a limestone belt, numerous caves and caverns had been formed in the Paleozoic era, several of which were so impressive that they were opened to the public and became paying operations for their owners.

Below Vallecito, Coyote Creek flowed through the Natural Bridges, where water eroded the limestone, creating caverns with impressive stalactites and stalagmites. Mercer Caverns, “discovered” by Walter Mercer in 1885, had initially been explored by prospectors, but as they didn’t contain gold, no one publicized the find.

Thus began the role Murphys was to play as the tourism center for visitors to the Calaveras Big Trees, Mercer’s Caverns, Moaning Caves, Natural Bridges, San Antonio Falls, and other natural wonders of the region.

After slumbering for several decades, Murphys, like many other towns in the California Mother Lode, began to reawaken with the renewed interest engendered by the Centennial celebrations held throughout the state in 1948-1950. Books were written, photographs were taken, pageants were performed, tours were conducted, and the towns were publicized in a way that they hadn’t been since the days of the rushes for gold. Ghost towns became popular, and there was a renewed interest in mining and winegrowing.

Although Murphys developed slowly at first, with a few homes restored and many more demolished, the last decade has been one of unprecedented growth and development. Spurred by the establishment of Stevenot Winery and the others that followed in its wake, the town has now spawned an unprecedented amount of shops, stores, restaurants, inns, and other amenities that rival the days of ’49.

Walk around town, look around you, and do visit the Murphys Museum, founded by historian Coke Wood, the man most responsible for raising public awareness of the “Queen of the Sierra.” The town of Murphys offers an exciting history that is evident around every corner.

By Judith Marvin, January 2003.

References

Beauvais, A.B. 1876 Map of Murphys, Calaveras County, Cal. On file, Calaveras County Surveyor, San Andreas.

Calaveras, County of. var. Deed Books; var. Assessor’s Roll Books; var. Board of Supervisor’s Minutes; var. Road Books.

Fuller, Willard P, Jr., Judith Marvin, and Julia G. Costello. 1996 Madam Felix’s Gold, The Story of the Madam Felix Mining District, Calaveras County, California. Foothill Resources, Ltd., and the Calaveras County Historical Society.

Hoover, M.B., H.E. Rensch, E.G. Rensch and W.N. Abeloe. 1990 Historic Spots in California. Stanford University Press, Stanford. Revised by Douglas E. Kyle.

Marvin (Cunningham), Judith. 1981 National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form for Murphys.

Wood, Richard Coke. 1952 Murphys, Queen of the Sierra. Calaveras Californian, Angels Camp, California.

Wood, Richard Coke. 1955 Calaveras, The Land of Skulls (The Calaveras Country). The Mother Lode Press, Sonora.

United States Geological Survey. 1948 Murphys, Calif., 7.5 minute topographic quadrangle.