Carson Hill

Carson Hill, Camp and Creek were named for James H. Carson who first reached the area that was to bear his name in August, 1848. Carson had been a Second Lieutenant in Col. Jonathan D. Stevenson’s Regiment of New York Volunteers, mustered out in the summer of 1848 in San Francisco. The news of the discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill found the members of the Stevenson’s Regiment in an ideal position to be among the first Americans in the mines of California. Carson left immediately for Placerville and then traveled southward to Carson Hill with a company of 30 men, many of them Mexicans. Reputedly, Carson “discovered” the placers on Carson Creek with the assistance of an Indian who told him that he could find gold there.

Within ten days Carson and a small company had each taken out 180 ounces of gold; they left the area that fall (Carson 1950:8). By the middle of December, 1849, a traveler was to comment: "We passed by Carson’s Creek where there were no miners then, though Jim Carson had discovered gold there previously” (San Andreas Independent: Sept. 18, 1858). In November of 1849, only 29 men voted in the election held in the Carson District. But upon Carson’s return to the area in that year, he commented upon the change:

When we reached the top of the mountains overlooking Carson’s and Angels Creeks, we had to stand and gaze on the scene before us–the hillsides were dotted with tents, and the Creeks filled with human beings to such a degree that it seemed as if a day’s work of the mass would not leave a stone unturned in them (Carson 1852:17-18).

This early period of mining in the Carson Hill vicinity was characterized by individual miners on small placer mining operations, using ground sluicing and working the streams with long-toms and rockers. It wasn’t until November, 1850, that a strike in the rich quartz vein on Carson Hill was confirmed. There are two accounts of the discovery. The popular version states that a company of miners including John (William) Hance, William S. Rowe, Alfred G. Morgan, James Broome Smith and others discovered the vein on October 20, 1850. According to an anonymous account of the discovery, Hance’s mule had strayed from his placer in Carson Creek. While following it to the top of the hill he “saw a yellow piece of metal on the top of a little column of quartz," and broke off a 14 pound “nugget” with only a rock (Anonymous ca.1903:1).

Another version argues that it was a Mexican by the name of Pacheco who discovered the ledge of gold-bearing quartz. According to Alexander Lascy, a miner in the area at the time:

An old Mexican miner, Pacheco by name, found traces of gold in the croppings of the quartz on the summit of the hill, which he deemed to be valuable for further exploration, and wishing to claim them told several Americans about it. Among them was one Broom Smith (Lascy:nd).

Lascy’s account is probably true, since the Mexicans were the more experienced miners and were used to mining goldbearing quartz ore. Credence is lent to the story by the Calaveras County Assessment records for 1857 which assessed A. G. Morgan & Co. for a quartz mill and the “Pacheco Shaft.” In any case, the claim became a sensation. It was known hereafter as the Morgan Mine, after Morgan, a codiscoverer and one of Carson’s compatriots in Stevenson’s Company. J. Ross Browne, who reported on western mining statistics to Congress, wrote that between February 1850 and December 1851 over $2,800,000 worth of gold was taken out of the Morgan Mine (Browne 1869:59). Around this time, the Scottish visitor J. D. Borthwick recorded his impressions of Carson Hill:

From Angels Creek I went on a few miles to Carson Creek, on which there was a small camp, lying at the foot of the hill, which was named after the same man. On its summit a quartz vein cropped out in large masses to the height of thirty or forty feet, looking at a distance like the remains of a solid wall of fortifications. It had only been worked a few feet from the surface, but already an incredible amount of gold had been taken out of it (Borthwick 1917:306).

The Alta California, a popular San Francisco newspaper, first mentioned the find on 25 April, 1851:

From Carson’s Creek For the past few days a vague and undefined rumor has been in circulation in town, which we cannot trace to any reliable authority, that an extraordinary discovery of gold has been made in the above locality. Rumor says that as high as $200,000 has been taken out and that the vein still leads into the rock without any diminution of its size and quality. The lead is described as being six inches in thickness of pure gold (In Jackson and Mikesell 1979a:7).

On May 24, 1851, the Sonora Herald repeated this same rumor, also indicating that a portion of the diggings at Carson Creek were known as “Maloney’s” (Melones):

Carson Creek –There have been rumors in town for the last few days sufficient to startle the imagination even of Baron Munchausen, of the extraordinary deposits of gold just discovered at Carson’s Creek, and at Maloney’s diggings (in Jackson and Mikesell 1979 a:8).

Word of this discovery precipitated a rush to the Carson district. While the Americans lived in the rapidly growing town of Carson Hill, the primarily Mexican workforce had their own settlement, nearby Melones. The Mexicans’ prior experience with quartz mining made them invaluable to the Yankee mine owners. According to Browne:

The news filled the State with excitement. The town of Melones, on the southern side of the hill, became the largest mining camp in the State, with a population variously estimated from 3,000 to 5,000 (Browne 1869:59).

Undoubtedly “Mexican” Melones was an important mining camp in 1850, but the accounts of the time don’t mention anything approaching a population of several thousand. Undoubtedly the number was quite inflated—typical of the sensational journalism of the day. (The “Mexican” Gold Rush town of Melones should not be confused with the later renaming of Robinson’s Ferry to “Melones” in 1902 [see Jackson and Mikesell 1979a]).

According to the diary of Leonard W. Noyes

The whole hill was worked by Mexicans hired on shares and a Town called Melone was started on the opposite side of the Hill from Carsons (taking its name from the fact of the gold found in Carson Creek was in the shape of Mellon seeds). This place called Melones was built of Brush streets say 10 feet wide lined on each side with these Brush houses where Gambling was carried on at an enormous extent, all the Mexicans having money (Noyes nd:60).

Archaeological and historic research, as well as the reminiscences of Emile K. Stevenot, suggest that the camp “Mexican Melones” was located on the old Stevenot homestead on upper Carson Creek, which was always referred to as the “Melones Ranch” (Jackson and Mikesell 1979:26). Although at its height Melones was thought to be the largest mining camp in California, it apparently existed only a little over a year.

Carson Hill was virtually abandoned only three years after the strike when the quartz mines were shut down in legal disputes. The Morgan Mine was undoubtedly the most important one on the north side of Carson Hill, said to have realized over $3,000,000 in gold in its first two years of operation. Its closure due to legal entanglements in 1853 turned this thriving Gold Rush community into a ghost town overnight.

The fight over ownership of the Morgan Mine property has received a great deal of attention in the historical literature, with the result that a great deal of misinformation has been handed down. Hubert Howe Bancroft, one of the foremost California historians, tells two different stories of this incident in his California Inter Pocula. One version is that the quartz vein on Carson Hill was discovered by Alfred Morgan in 1850 and that he was driven off the property by miners who questioned his right to the claim. The second story is that Hance and Finnegan found the mine in 1849. Finnegan went East to purchase machinery, and when he returned two years later he discovered that Hance had sold the claim to Morgan and absconded with the proceeds. Finnegan sought the aid of other miners, and with their help he drove Morgan from the mine in December of 1851. Morgan went to the courts to seek redress, and eventually was declared the rightful owner. But the local miners rejected the judge’s decision and armed themselves to retake the mine (Bancroft 188b:273-240).

The primary documents seem to support Bancroft’s second explanation. In the thick of the battle over ownership of the Morgan Mine, a resident of the area wrote to the Alta California to express his point of view:

Sirs: On this subject I know one Hance, who together with two other persons, discovered in 1849, the quartz mine on Carson Hill, and worked it jointly for eighteen successive days, when at the suggestion of Hance, Finnegan, one of the three, went to the States with a view to effect arrangements to bring out machinery to work the mine with, and much to his (F’s) disadvantage, while absent, Hance with the cunning of a fox gets Morgan & Co., capitalists, in connection with him, and works the mines contrary to all arrangements with the other partners, takes out the enormous amount of one million dollars. Hance, on the first news of Finnegan’s return, pockets a large share of the amount taken out and clears for home, and at last accounts he started for London and Paris, where it is likely his ill got lucre will vanish, as all obtained by fraud is sure to do (Alta California:Dec. 24, 1851).

Another version of the Morgan Mine incident appeared in the San Joaquin Republican, about the same time:

The details of the important difficulty which has arisen on Carson Hill are in the shape of resolutions passed by the miners, and an address written by Alfred Morgan & Co. It appears that said Morgan & Co. (Col. Hays being a member,) located a quartz claim on the hill in October, 1850, the extent claimed was one thousand feet; that they worked the claim uninterruptedly nine months; that the precious metal was found in immense quantities; and in August, 1851, the miners of Carson Creek and its neighborhood held a convention at which they passed a resolution reducing the extent of Morgan Co.’s and other quartz claims. From this moment the dispute alluded to commenced. Morgan & Co. resolved to maintain their claims to one thousand feet, and the miners resolved that they would not allow so large an area, and were determined to carry the resolution they passed. The cause was tried before Judge Putney, at Murphy’s, and there the decision was adverse to the interests of A. Morgan & Co. An appeal was taken, and the case was again argued in the County Court, before Judge Smith, who reversed the decision of Judge Putney. Notwithstanding this, however, the disaffected parties of Carson’s creek and hill, resolved that inasmuch as the late decision was contrary to the law they had passed in August, they would oppose force to the demands of Morgan & Co., but the same night a number of miners again forcibly took possession of it, and on Thursday 200 persons, well armed, headed by Finnegan Vanderslice, Laing, and others gave Morgan & Co. one hour’s notice to quit the premises. Morgan & Co. left, and the others took possession (San Joaquin Republican:Dec. 22, 1851).

It is interesting to note that both the above stories mention a man named Finnegan being involved in the Morgan Mine controversy. It is unclear, however, exactly when the discovery took place, and whether Finnegan actually was with Hance at the time the claim was found. The misinterpretation of these events was revealed by historian Paul Friedman (Friedman 198 :21). The error began in 1867, when a reporter for the Alta apparently confused the name Finnegan with Billy Mulligan. On 17 June 1867, the Daily Alta California printed the following explanation of the Morgan Mine battle: "The mine was too rich to be enjoyed in peace. A gang of several hundred ruffians, headed by Billy Mulligan, and others like him, came and drove away the owners, and worked the mine for nine months, at the end of which time they were stopped by an injunction, and seven months later they were driven away" (Jackson and Mikesell 1979a:24).

Billy Mulligan was an infamous figure in San Francisco history who had run afoul of the vigilance committee. There is no evidence that he was in the southern mines at the time of the Carson Hill episode. Unfortunately, this bit of misinformation found its way into history, through J. Ross Browne, considered to be an accurate informant on California mining, who borrowed the Billy Mulligan story from the Alta.

The 4 June 1852, edition of a San Francisco journal called The Pacific reported the demise of “Mexican” Melones:

A multitude of people was drawn hither by the excitement. They were scattered along the ridges and sides of the hill, running shafts into the rock in search of some golden vein. At night they formed a large encampment nearby where the prospects of the day were talked over, and the mirth and revelry ran high. That encampment, called by the Spaniards, Melones, is now silent and deserted. One old Mexican is found there watching the barley that has sprung up from last year’s waste in horse lots that then were worth thousands of dollars each. The multitude has gone (The Pacific:June 4, 1852).

John Heckendorn, in his Miners and Businessman’s Directory. also recalled the closing of the Carson Hill mines:

In 1851 this was the great Camp of the South–thousands rushed there to get a chance at the Mountain of Quartz, said to contain Gold sufficient for half the world. Companies were formed, claims taken up, and men put to work upon them; disputes arose as to boundary lines, and there were a general war in consequence of these misunderstandings; several persons were killed, many of the claims were thrown into litigation, and cost thousands before decisions could be had as to who was the real possessors. But few of the claims are being worked at this time but soon as the proper means are employed, no doubt but they will be the most valuable property in California (Heckendorn 1856:97).

A writer for the San Andreas Independent visited the area in November, 1857, and described its dull and ruined appearance:

Carson’s Creek–The usual general apathy (and by the way, he is a general of five years standing in this vicinity), prevails at Carsons. Mr. Carlow, the village black-smith, as usual, “tells his quaint stories,” while the miners’ laugh is ready chorus. The shovel, pick and pan lie rusting by the chimney, and the padlock hanging listlessly on the cabin door, is a silent monitor that the vitality of the mercantile world gold has ceased to be profitably extracted from the hills and gulches around Carsons. This old hill, once so famed on account of the rich Meloney quartz claim, is not now worked. When water is plenty, a few claims near the Creek, are worked with tolerable success. Both of the quartz mills are idle; and no water to even prospect the gulches (San Andreas Independent: Nov. 7, 1857).

In the spring of 1853, final legal judgement was rendered in favor of Morgan and his associates. Morgan then went to England to sell the mine, making a provisional sale for $4,500,000. During 1857, Morgan and Rowe were assessed for $11,075 as the value of the Pacheco Shaft. By 1858, they had constructed a “1O-stamp steam power, 20 horse mill.” The following year it was leased to A. J. Ellis & Co., along with the house and stable. By 1860, they were assessed for a horizontal boiler, blacksmith shop and tools. More litigation sprang up about the title and little work was done until the spring of 1867 (Browne 1869:60).

In October of 1869, the mine was sold for back taxes to William Irvine for $115.19. Litigation with James G. Fair, Henry D. Bacon and others continued until March 9, 1874, when a patent was issued to William Irvine. An attempt was made to work the mine, but not enough capital was forthcoming and in 1875, Irvine deeded the claim to the Morgan Mining Company of which he was a major stockholder. In April of the following year, Irvine and Dr. Robert McMillan were issued a patent on 25 acres of placer mining ground surrounding the Morgan Mining Co. claim. Irvine and McMillan divided their holdings, Irvine retaining the portion in the front of the mine which he also deeded to the Morgan Mining Company. By November of 1877, Irvine had acquired the controlling interest in the Morgan and worked out an easement giving the Company the right to use the ground of the Carson Hill Mill and Mining Company for running tunnels and sinking shafts, dumping of ores, and other mining operations.

About 1876, the mine was reopened and a tunnel begun which, in 1878, struck the vein 200 feet below the outcrop. The mine operated intermittently until 1884, when Irvine built a new 10-stamp mill on the property, only to close it down after three months when controlling stock was obtained by James G. Fair, the man behind all of the litigation on the mine since 1871. Long-standing animosity between Fair and Irvine resulted in a disaster for the mining operations.

Senator Fair closed the Morgan Mine and refused during his lifetime to allow the mine to be worked, so that Irvine would not recognize a profit from his 25% interest. It wasn’t until 1914, when the Calaveras Consolidated Mining Co. bought the Morgan Mine from the Fair estate, that the mine was reopened.

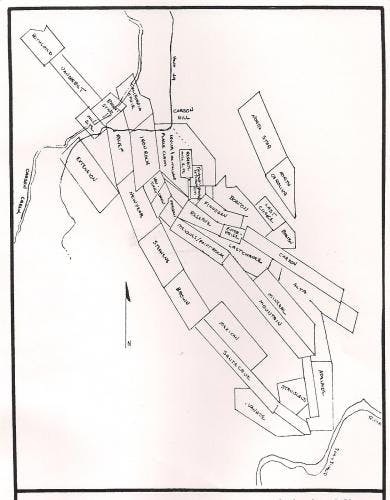

While the Morgan Mine was the most important mine on Carson Hill in the 19th Century, there were other mines with considerable mining activity, if not always a great deal of production. In October of 1852, members of the Old Dominion and South Carolina Mining Companies resolved their disputes over claims by forming an agreement and vesting their power of attorney in T. Butler King to negotiate for the sale of claims “to capitalists” (Calaveras County Records, Miscellaneous 1852:143, 166, 168). Although the sale evidently took place, there is little mention of these mines in historic documents (except for an 1870 assessment to the Carson Hill Quartz Mining Co.), until much later when in 1896 three tunnels and several crosscuts were driven by the Melones Mining Co., which held the property under bond for the Melones Consolidated Mining Co. In 1903 a twenty-stamp electric-power mill was constructed just north of and below the main adit. In 1916 the mine and mill were being operated as the South Carolina Company with T.A. Perano as manager. Later, the South Carolina became an important claim of the Melones Consolidated Mining Company, although the mill building had disappeared by 1926 (W.C.Ralston:1899).

In 1852, S. R. Bonner and Henry Vanderslice also negotiated an agreement with Manuel Rubio whereby he was to work their mine, divide the gold and valuables, and build a mill out of the proceeds of the mine (Miscellaneous 1852:51). The outcome of this venture is also lost to present historians.

On November 22, 1854, the largest mass of gold ever found in the United States, the “Calaveras Nugget,” was taken from the Comstock claim on Carson Hill by four Americans and one Swiss miner. It weighed 195 pounds troy and was valued at $43,534. It was purchased by a man from New Orleans, exhibited at the French Exhibition in Paris in 1856, and apparently melted down shortly thereafter (Costello 1983:13)

In April, 1858, new diggings were discovered at Carsons:

On the slope of the steep hill which leads up to the “Maloney Quartz Lode,” extensive and rich diggings have been discovered. Several acres of ground are now being worked, from ten to twenty feet in depth, which will pay from six to twenty-five dollars per day. Water now being plenty, other claims, equally rich, are being extensively worked, and business generally, in the place is looking up (San Andreas Independent:April 10, 1858).

In 1858 a journalist for the San Andreas Independent mentioned the “crumbling remains of stone chimneys and adobe ovens” and the “little level plats where once stood tents and dwellings.” However, he also noted the recently developed claims of Messrs. Boden & Co., Sutherland & Co., Gore, Bickle & Co., and Rowe and Co., all working “by cars upon railroads.” He visited the steam mill of the Morgan mine, operated by Rowe & Co, and leased by A. J. Ellis & Co., and noted that the Finnegan & Co. mill on Carson Creek was being leased to Messrs. Reynolds, Hutchinson & Co., who were “putting it into repair” (San Andreas Independent:April 24, 1858).

By April of 1859 the same correspondent mentioned several claims on the north slope being operated by Horton, Gilmartin & Co., Sutherland & Co. and Sherman, Smith & Co., in addition to the rich Finnegan claim on Quartz Hill. The Morgan & Co. mill was idle. Water was supplied to the area by the Eureka Ditch. Hamilton & Co. had provided a flume to the flat between the town and the Quartz Hill where a company of Italians was ground sluicing (San Andreas Independent:April 23, 1859).

By 1864 the Union Mine was operating a 20-stamp steam-power mill on Carson Hill. This mine and mill were awarded in December, 1871, to Dr. Robert McMillan of San Francisco in satisfaction of a judgment for $10,225 against the Carson Hill Union Mining Co. The improvements on the site included a quartz mill, office, blacksmith shop, boiler, engines, barns, cart and tracks. Dr. McMillan was also the owner of the Kentucky Mine and by 1889 the mill had became known as the Kentucky Mill, probably due to a consolidation of the properties. By 1891 James G. Fair had gained control of the mine and mill which were assessed for $2000 in improvements, but by 1902 the estate of J.G. Fair was only assessed for an “old mill” with a value of $250.

In 1866, Finnegan had constructed a six-stamp, steam operated mill on his claim and The Sonora Democrat of 1867 stated that the people of Carson Hill had reason to expect “a good time coming. Two quartz mills–one of five stamps, the other of twenty stamps, are now running; and another of ten stamps will be completed in a month. We hope they will keep business at Carson Hill in perpetual motion” (Democrat:1977).

This was not to occur, however, as during the 1860's and 1870's the mines were idle much of the time as a result of continued lawsuits and milling difficulties. Lack of modern processes, absence of a cheap labor force, and the necessity for large scale operations made it expensive to mine and mill the low grade ore. This lack of large-scale mining development, however, was conducive to pocket mining and prospecting by independent miners. David C. Demarest, Calaveras mine owner and foundry operator, described activities at Carson Hill during this period:

For the first half-century of its mining life, Carson Hill was a paradise for pocket hunters, both those who paid royalties to the mine owners, and others who neglected to do so. As indicating that the gold recovered by the latter may have reached a large figure, I recall one case in the late 1890’s, in which I was told by Tom Gibson, then a noted San Francisco detective, that he had traced secret shipments to the United States Mint, of gold aggregating over $30,000 from one miner on the Hill (Demarest Ms., Box 1, Folder Dl: in Greenwood and Shoup 1984:67).

In 1876 the Morgan and Melones mines were reopened and operated intermittently through the 1880’s. During the 1870’s Gabriel K. Stevenot, a French mining engineer who had settled in the area in the early 1850’s, began to patent many of the claims on the hill and consolidated them into one group. Stevenot had reportedly brought the first stamp mill to the Carson area in the early 1850’s, setting it up on Carson Creek and milling the ore from his Reserve mine, adjacent to the Morgan. This stamp mill was washed away in the flood of 1862. Stevenot continued to be involved in the mines of Carson Hill during his lifetime, finding a rich pocket in the Stanislaus mine in 1876, and acting as agent for the first major consolidation of mines on the hill.

In 1888 the Calaveras Consolidated Gold Mining Co., also known as the “Old English Company”, was organized in London. This company purchased the Stevenot claims and others with the aim of processing a large volume of ore, retaining Gabriel Stevenot as mining superintendent. This was the first instance of the infusion of a large amount of risk capital by an international company in the Carson Hill mines. The consolidation included the New York (Finnegan), Stephens, Brown, Santa Cruz, Mexican, Extension, Relief, and Calaveras claims. A 20-stamp mill, operated by Pelton wheel, was constructed on the Santa Cruz with an electric plant for lighting and pumping. Work began by drilling an adit into Carson Hill on the Calaveras claim to penetrate to the Relief claim. Initially, good ore was found, but was soon lost. The mills closed in 1892, after only a few years of operation. This was, however, the first operation in the area in which low-grade ore bodies were mined in volume (Clark and Lydon 1962:42).

In 1898, a United states Government Geologist visited the area and discussed the ore bodies:

Southward from Angels Camp, no more important mines are met until Carson Hill and Robinson’s Ferry are reached. On the south slope of Carson Hill there are at least three strong and distinct veins, all more or less curved. They lie chiefly within fissure amphibolite-schists, although some of the ore bodies are accompanied by small dikes and streaks of black slate. The Carson Hill Mines were extensively worked in the early days and the ore bodies were found to be very rich in their upper portions. There is at present, however, no deep mine in paying operation, although prospecting on an extensive scale is in progress, and it is likely that one or more large mines may soon be working in this noted locality, treating low-grade ores by modern processes (0. S. Geological Survey 1900 in Greenwood and Shoup 1984:68).

The U. S. Geologist’s portent was to prove true. By 1895, plans were made for a new large-scale mining operation. Significant for this enterprise were the availability of new processes and equipment, including cyanide refining and improvements in stamp mills, concentrating machinery and underground mining technology. The introduction of dynamite and air drills. the development of electric power, and ambitious new U.S.-based promoters and investors also provided impetus for what was to become one of the most successful mining operations in Calaveras County, and a most important one in California.

In 1898, the Melones Consolidated Mining Company was formed. It was financed primarily with Boston capital and was organized with William Ralston as agent and William Deveraux as superintendent. This concern consolidated the Enterprise, Keystone, Last Chance, Melones, Mineral Mountain, Reserve and Stanislaus claims, and later added the South Carolina. They drove a new adit from the Stanislaus River for ore haulage to the proposed stamp mill at Robinson’s Ferry. It took nine months to construct this one-half mile long “Melones Tunnel.” In 1899, a 100-stamp mill was planned; 60 stamps were completed by the fall of 1901, and 40 more were added by 1905. In 1902, the name of the river community was officially changed to Melones.

This was the first mine on Carson Hill to employ modern technological methods including a large mill and full electric power, with a substantial work force, and a deep mine from which large volumes of relatively low-grade ore were excavated. By 1910-1919, 14,630 feet of working drifts had been driven by the Melones Mining Company at Carson Hill. Compressed air drills were used to mine both the ores at the Glory Hole and underground. Electricity and power were provided from the Camp Nine Powerhouse on the Stanislaus River, supplemented by the Sierra and San Francisco Power Company.

Large quantities of ore were mined, 245,000 tons in 1918 with a recovery rate that was exceptional for its time. The total output of the Melones Mining Company was estimated at about $4,500,000. The ore was low-grade, but mining and milling costs were lower than at any other mine on the Mother Lode belt (Clark and Lydon 1962:47).

Although large-scale mining and milling operations shifted to the south side of Carson Hill at Robinson’s Ferry in the late 1890’s, there was still considerable activity around the town of Carson Hill. In 1914, the Morgan Mine was purchased from the James G. Fair estate by the Calaveras Consolidated Mining Company. Earlier some exploration work had been started in 1909 by an engineer for Virginia Vanderbilt, Fair’s daughter. He drove a tunnel into the hillside and built a compressor plant and blacksmith shop at the portal. In 1907, William Irvine’s son Louis and his wife Katherine sold the interests in their properties in Carson Hill to the Morgan Mining Company, retaining the mineral rights. These properties included several houses, the McMillan and Irvine Placer Claim on the Flat, and the Canepa/Oneto Store.

Meanwhile, in 1917, Carson Hill Gold Mines, Inc. was formed under the direction of W. J. Loring with A. D. Stevenot as mine superintendent. The old Morgan mine was purchased in 1918, and a new adit known as the Morgan adit was driven in a southerly direction from the north side of the hill. The Melones Mining Company closed in 1918 and sold out its Carson Hill properties. Loring then shifted over to the Melones adit. A new, rich ore body was encountered in schist in the hanging wall of the large massive “Bull” vein. This proved to be the upward extension of high-grade ore previously mined some 1300 feet below on the 1600-foot level. In the next few years, this hanging-wall ore body was mined to a depth of 4,550 feet and yielded more than $5,000,000. A new 30-stamp mill was erected at Melones west of the highway. Carson Hill Gold Mines, Inc. operated the properties until 1926; the value of the production for their 7 years of operation was estimated at $7,000,000 (Clark and Lydon 1962:47).

With the development of the Morgan Mine from the north side of the hill, activities increased at the town of Carson Hill. About 1910, a bunkhouse had been constructed on the flat and during the period 1917-1918, several dwellings, another bunkhouse, a boarding house, office and other structures were built on the original McMillan and Irvine Placer by the Company. In 1925, Carson Hill Gold Mines, Inc. owned numerous properties at Carson Hill including a dwelling, a post office with dwelling, bunkhouses, a change house, office, compressor plant, blacksmith shop, barn, and other small buildings, and a transformer house and hoist at the “Main Raise”. The mine was valued at $50,000 and the improvements at $10,000 (Calaveras County Assessments:1925).

During these years, the Finnegan mine was being operated sporadically by members of the Tarbat family of Carson Hill. At various times Bert Tarbat, Andrew Oneto, Tom Purdy and others prospected in the Finnegan and Melones veins, operating the old mill when sufficient ore was mined. In the mid-1920’s they were working the 1100-foot level with churn drills, placing wedges in the tunnel walls nightly to check for loose rock. One day they found the wedges loose and abandoned their claim. That night the whole hill caved in, creating the landslide in the open pit that is still visible today (Castle:1982).

Assessment records indicate that in 1928 a 10-stamp electric powered quartz mill, rock breaker, 6 concentrators, 2 compressors, electric hoist, blacksmith shop, compressor room, hoist rooms, mill building and mining tools were located on the Finnegan Mine and Finnegan Extension. This new mill was undoubtedly built by the Carson Hill Mining Company, which then owned one-tenth of the mine, under a lease agreement with the Tarbat family who owned the other nine-tenths (Calaveras County Assessments:1928).

By the early 1930’s the Finnegan Mill was on its last legs: one bunkhouse in the town was being used as a private residence, and individuals had purchased other mine company houses. The only mining activity was involved in de-watering the mine. Bailing was done by water skips at the 1100-foot level and took nine months to complete (O’Connor:1985).

In 1933, the Carson Hill Gold Mining Corporation was organized by A. O. Stewart with J. A. Burgess as mine superintendent. This time the promoters were all local individuals: Lawrence Monte Verda of Angels Camp, M. H. Manuel of Murphys, and Charles H. Segerstrom of Sonora. The Morgan and Melones mines were rehabilitated to the 3000-foot level where newly discovered ore bodies in the footwall area were exposed. These were mined from that depth to the surface, and eventually down to the 3500-foot level. It was at this period that the extensive pits were developed. These included the Relief, the Union Shovel Pit (Morgan Glory Hole), and the Footwall glory holes west and south of the Morgan Bull vein.

Milling was done on the Melones side of Carson Hill and the town of Carson Hill again declined in population. A few families who worked in the mine continued to reside in the community, some in the still-operating boarding houses. Many miners walked over the old wagon road on Carson Hill to their jobs in Melones.

The capacity of the 30-stamp mill at Melones was increased and numerous buildings constructed. 1939 was the peak year of production; $937,156 worth of gold was sold. On May 31, 1942, the mill burned to the ground, ending a mining era never since to be equalled in Calaveras County. However, this operation would soon have closed anyway, as in October of that year, the War Production Board was to enforce L-208, which closed all of the major mines in the Mother Lode. All activities at the Carson Hill mine ceased and many of the miners left the region to work in the war-related industries in the San Francisco Bay Area.

After the closing of the mines in 1942, many of the buildings in Carson Hill were burned or torn down and the few remaining ones became private residences. Today but a handful of people reside in Carson Hill and just a few stone or concrete foundations remain of the mills of yesterday.

By Judith Marvin (Cunningham)

History from the report by Julia G. Costello and Judith [Marvin] Cunningham, 1985, Archaeological and Historical Study of Carson Hill, Calaveras County. By Foothill Resource Associates for Carson Hill Gold Mining Corporation, Altaville.

References

Anonymous, 1903. The History of the Morgan Mine. Ms. on file, Carson Hill Gold Mining Corporation.

California Inter Oicula, 188b. Vol. XXXV of The Works of Hubert Howe Bancroft. The History Company, San Francisco.

Borthwick, J. D. The Gold Hunters: A First Hand Picture of Life in California Mining Camps in the Early Fifties. Edited by Horace Kephart. MacMillan, New York, 1917.

Browne, J. Ross. Resources of the Pacific Slope. Appleton and Company, New York, 1869.

Carson, James H. Recollections of the California Mines: An Account of the Early Discoveries of Gold, With Anecdotes and Sketches of California and Miners’ Life and a Description of the Great Tulare Valley. With a forward by Joseph A. Sulluvan. Biobooks, Oakland, 1950. Reprint of a Stockton edition of 1852.

Clark, William B. and Philip A. Lydon. Mines and Minerals of Calaveras County, California. State Division of Mines and Geology, San Francisco, 1962.

Costello, Julia G. Melones: A Story of a Stanislaus River Town. Bureau of Reclamation, Sacramento, 1983. U.S. Department of Interior.

Friedman, Paul. 04-Cal-S-315, Historical Overview. Draft Report of the New Melones Lake Project. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Sacramento, 1980.

Greenwood, Roberta S. and Laurence H. Shoup. Robinson’s Ferry/Melones–History of a Mother Lode Town, 1848-1942. Final Report of the New Melones Archaeological Project, Volume VIII. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C., 1984.

Heckendorn and Wilson. Miners and Businessmen’s Directory. The Slipper Office, Columbia, 1856. Reprinted by the Tuolumne County Historical Society in 1976.

Jackson, W. Turrentine and Stephen D. Mikesell. Mexican Melones. Las Calaveras, 28 (1): 1-16, 1979.

Noyes, Leonard W. Journal and Letters. Ms. on file, Essex Institute, Salem, Massachusetts, n.d. 1850’s and 1880’s.

Ralston, W.C. note of the Cost of Tunneling at the Melones Mine, Calaveras County, California. Transactions of the American Institute of Mining Engineers 28. February 1898 to October 1891, New York City, 1899.

Castle, Guy: A miner who worked in the Carson Hill Gold Mines from 1933 to 1942; he is presently still doing some work in the mine. Contacted June 1985.

O’Conner, Oliver: A miner who worked in the Carson Hill Gold Mines from 1930 to 1942. Contacted June 1985.