Cattle in the Sierra

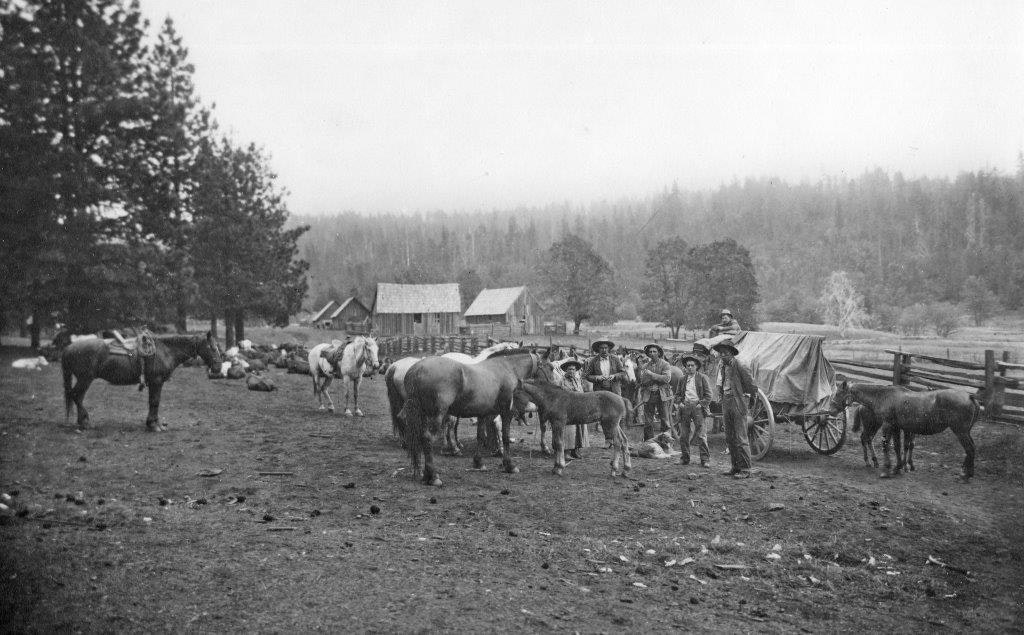

Historic Sierra Nevada summer cattle ranges adjust to the modern era.

Since the 1848 discovery of gold in California, livestock have summered in the green highlands of the Sierra Nevada, returning to their foothill home ranches in the fall. Iconic images of annual drives and roundups are part of our Western heritage. This annual pattern (transhumance), however, is rapidly disappearing. Unstable beef prices, difficulties in trucking livestock to summer ranges, and environmental regulations, threaten to eliminate livestock from our National Forests. Grazing allotments– like mining and logging permits, and access by recreationists and hunters – are part of the intended use of these public lands. Livestock browse flammable brush and keep meadows open, while home ranches preserve foothill landscapes. Opponents to grazing cite degradation of streams and meadows and the intrusion of cowbells and cowpies in an alpine setting. Ranchers with grazing allotments are now subject to strict regulations adopted in the 1990s, and most work to be good stewards of their lands. Grazing opponents, ranchers, and the Forest Service can work together to preserve both natural landscapes and this historic economy.

Cattle ranching has been the primary agricultural industry of Calaveras and Tuolumne Counties for 160 years.

By 1854, developed cattle ranches in the Mother Lode supplied quality fresh beef, butter, and fresh milk to miners and their families at good prices.. As the easy gold disappeared so did the miners, and between 1860 and 1870 the Mother Lode lost half its population, shifting the economy to stock-raising. The severe drought of 1861-1864, however, decimated the herds. Cattlemen who survived found a limited supply of summer feed available in the high country. although difficult to reach, it assured the survival of cattle ranches in the foothills. Today, cattle and calve production is the bedrock of Calaveras and Tuolumne County agriculture, sustaining ranching families, feeding the local economy, and preserving open space for grass, trees, and wildlife.

Free-ranging livestock ended with leased allotments by the U.S. Forest Service in 1905.

The Stanislaus National Forest Reserve was established in 1905 under the Organic Act of 1893. In contrast to National Parks which preserve landscapes and historic sites, National Forests were established for the public to extract natural resources through logging, mining, and grazing. The mission of the Forest Service is to “sustain the health, diversity and productivity of the Nation’s forests and grasslands to meet the needs of present and future generations.” With the advent of the Forest Reserve, cattle and sheep that had previously roamed free over the Sierra Nevada ranges were assigned to individual leased allotments. In the early years, herds were driven up to summer pastures where ranch families frequently stayed the season, residing in cow camps and cabins. Many Sierra reservoirs were developed initially as stock ponds. With the allotments came the addition of fencing and increased emphasis on range management.

Beginning in the 1960s, urban recreationists have advocated against livestock degradation.

The biggest change to occur in the National Forest since its inception is land use. Years ago it was only hardy recreationists who came to the mountains to hike, fish, hunt, and partake of outdoor life. With the advent of the automobile and the growth of cities, more and more people came for recreation: hiking, hunting, fishing, solitude, camping, and horse-back and motorcycle riding. These new forest users were also of an era engaged in environmental protections. They reported overgrazing, stream degradation, and manure. The Forest Service responded. In the 1990s, assisted by the U.C. Davis Rangeland Watershed Laboratory, the Forest Service and its scientists began implementing new regulations for the allotments. These included reduction of the number of cattle, specifying a minimum grass height in meadows, setting dates for beginning and ending grazing seasons, providing water and salt licks away from running water, and fencing off environmentally sensitive areas. Most ranchers have been good stewards of the land, but a few who haven’t followed management guidelines compromise National Forest use for all.

The earliest management of the Sierra Nevada by Native Americans..

Anthropologists and biologists have established that the Sierra Nevada landscape was managed by Native Americans for thousands of years. In prehistoric times, people resided in foothill villages in the winter and, beginning in late spring, followed deer herds to the high mountain meadows. Departing the high country in the fall, Native Americans traditionally burned the brush behind them, preserving stands of healthy timber and encouraging shoots of new spring forbs, grasses, and brush. Many early cattle ranchers followed this practice of fall burning. Following the Forest Service’s prohibition of seasonal burning, meadows filled with encroaching trees, ponds and watercourses dried up, brush and dead slash prevailed, and the forest became a tinderbox. Only recently have forest stewards reestablished the practice of controlled burning to maintain a healthy forest. Forest Service personnel have also begun educating the public on the value of livestock for maintaining open ranges, reducing fuel loads, and opening up meadows rapidly being encroached upon by young seedlings.

High country grazing and low country ranches are mutually dependent.

The preservation of rolling foothill grasslands can depend on continued use of high mountain meadows for summer grazing. If ranchers are barred from transhumance, many may be unable to sustain their herds in the summer months when grasses dry up. The current pattern in the foothills is for former family ranches to be turned into developments with the accompanying loss of oaks and grasslands. The continued viability of small family ranches helps to preserve the open, historic and ecologically diverse landscape of the foothills.

A win-win for all is what is wanted.

As observed by Sue Forbes, retired Stanislaus National Forest Rangeland Manager:

“It sounds like sometimes that we all want something different, but really when people sit down together and talk about what it is they want, the ranchers and the environmentalists, and really the public that uses this Forest, really want the same things. And once they can sit down and talk about the things that they have in common and they start brain-storming about what they can do to keep those things, a lot of those issues go away and we start working together in a more productive way. … So my view is that it may be a hard road and sometimes it’s a give-and-take and we’ll find ways to do it better, but I think we’ll resolve those issues.”

This text was developed by Judith Marvin and Julia Costello as part of a grant by California Humanities to address current concerns involving cattle grazing on public lands in the Sierra Nevada. It was displayed at the Old Timer's Museum in Murphys, in 2018.

Also produced as part of this grant was a 16-minute documentary film: