Mining on the Mokelumne River

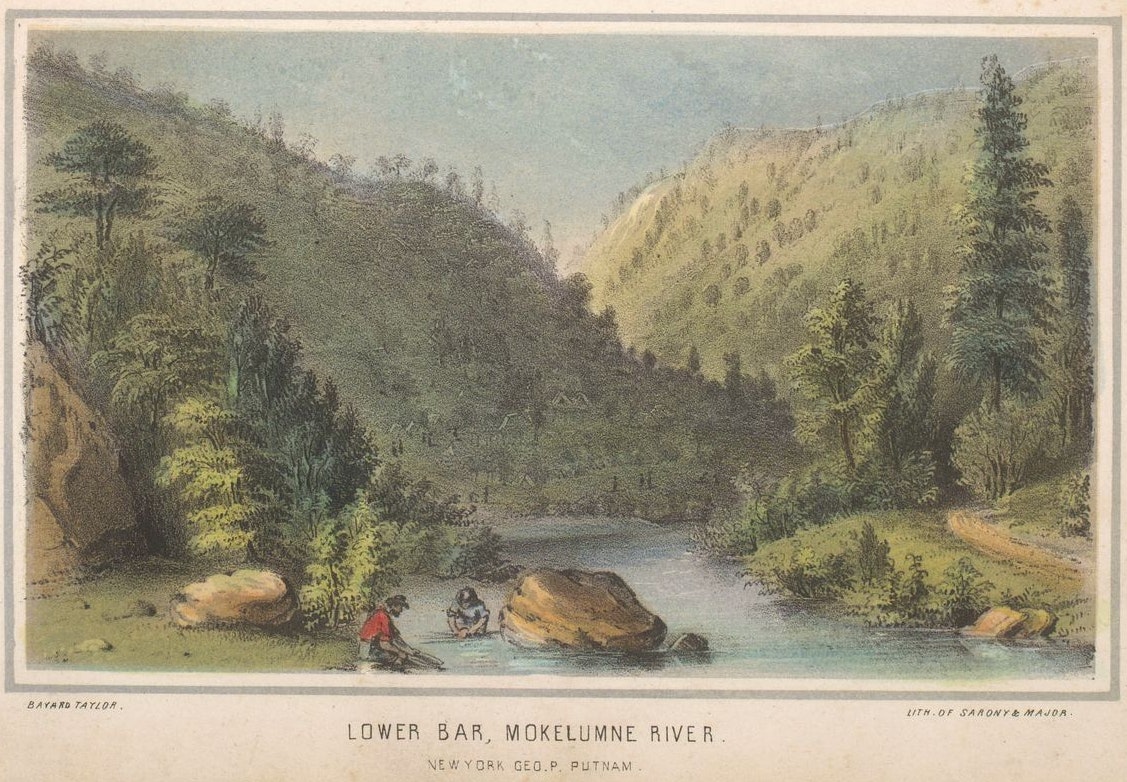

Placer mining began on the Mokelumne River in the earliest years of the Gold Rush, and camps were soon established along the river at Lancha Palana, Winters Bar, Oregon Bar, James Bar, and Middle Bar. Credit for the discovery of gold in the Penn Mine area, however, goes to a group of Mexican miners in 1849. Undoubtedly working their way up side gulches they encountered from the river, the men made their discovery on Oregon Gulch, which runs west through Campo Seco and empties into the Mokelumne River at Oregon Bar.

Rich placer ground was soon located on top of the hills, in gravel deposits left by the ancient Tertiary Era Calaveras River system. Miners who worked the Mokelumne River bars moved up into the hills and gulches during the winter months when the river water was too high, originally carrying the gravels down on mules and washing them in the river and other water courses. In order to work the deposits successfully, vast amounts of water were needed and the miners set about finding a source. With the completion of the Mokelumne Hill Canal and Mining Company system to the area in 1854, they were able to work the hilltops, leaving behind huge waste piles of stream boulders, gravel, quartz, and sand. Small hydraulic pits were also developed, and entire hillsides washed downstream.

By December of 1853, mining had become so important that the miners adopted a code of mining laws and defined the boundaries of the Campo Seco District as: "On the north by Salt Gulch, on the west by the Mokelumne River, on the east by Cosgrove Creek [sic, Cosgrove Creek], and on the south by the gulch known as Minter’s Gulch" (2). Gulch claims were 100 feet up and down the gulch and 25 feet wide. Upon flats claims were 100 feet square. On hill diggings, 75 feet square was the size of the claim (Las Calaveras 4[2:2]).

By 1855 small mining communities had been established at French Hill and Ragtown but Campo Seco remained the commercial center of the area, and the town flourished. A fire in 1854 destroyed much of the town, but it was quickly rebuilt. At one time it boasted a bank, many saloons, gambling halls, stores, hotels, a brewery, and a large Chinatown. Another fire in 1859 devastated the town, but by 1860 it had again rebuilt and then contained “a few fine gardens, two churches (one used for a school house), two large hotels (one of stone), a number of saloons and five stores. Water for domestic and irrigation purposes was provided from the Mokelumne Hill Canal (Las Calaveras 4[21:3]).

By 1857 most of the richest and readiest placer mining diggings had been exhausted and in 1860 the town was noted as “dull” (San Andreas Independent, August 25, 1860). When the government surveyor visited the area in the late 1860s, he noted many of the workings as "old mines": The hydraulic mine was also depicted, but had probably ceased operations by the time of his visit (Figure 6; General Land Office 1869a, 1869b).

Placer mining continued in the district, but by Chinese miners who reworked the early placer mines of the Anglo-European miners, who had since moved on to richer diggings elsewhere. During the 1890s several placer mining claims were again filed on the hilltops (Figure 7; Calaveras County Patent Map), and in the Depression era other small operations reworked the placers.

The discovery of copper ore, mistakenly thought to be gold, by two Mexicans and a Chileno in 1859, precipitated the major rush to the district and was responsible for the continued development of Campo Seco. The onset of the American Civil War, which required immense amounts of copper for shell casings and ammunition, created a boom in the mining district as copper claims were filed and mills and smelters erected.

One of the earlier claims was the Lancha Plana, later renamed the Satellite. Other nearby claims, located on Star Gulch, included the Campo Seco, Hecla, Constellation, Little Satellite, and others. All were shut down in 1867, however, when the copper need from the Civil War ended. Sporadic work continued through the 1870s and 1880s until the Penn Chemical Works acquired the Campo Seco claim, later purchasing the adjoining Satellite and Hecla mines as well, merging them into what is now known as the Penn Mine. This company constructed a smelter in 1899 and continued in operation through 1919, when the decrease in copper prices at the end of World War I forced closure.

Several small and short-lived projects were conducted during the 1920s and 1930s, until the mine was again operated on a major scale by the Eagle-Shawmut Mining Company from 1943-1946. In 1948 the Penn Chemical Company again commenced operations and continued production until 1953. Some work was done in the mid-1950s, but operations were suspended in 1959 (Clark 1962:28-29). The mine has been idle since except for some testing and exploration work.

By Judith Marvin, 2006